Transforming Urban Education

Understanding the Challenges Facing Inner-City Schools

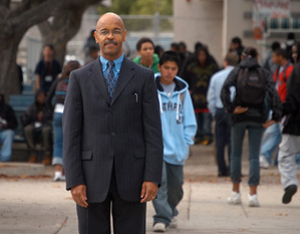

When Joe Johnson visits the campus of Monroe Clark Middle School in San Diego’s City Heights, he gets a warm welcome from teachers and office staff— even the cafeteria workers.

But Johnson doesn’t work for Monroe Clark or the San Diego City School District. Johnson is director of San Diego State University’s National Center for Urban School Transformation (NCUST), which is working closely with Monroe Clark and other inner city schools nationwide to help them bridge the growing gaps in urban education.

Urban schools like Monroe Clark are often plagued with low test scores, poor attendance, lack of resources and little parental involvement. Joe Johnson is constantly creating ways to overcome these problems — and convincing educators that it can be done.

“A lot of educators look at the enormous challenges facing urban schools and think academic success is as good as it's going to get, but it is possible to get better results,” Johnson said.

NCUST, created as part of the Qualcomm Institute for Innovation and Educational Success at SDSU with a $15 million endowment from the company, seeks to transform urban schools at or below acceptable standards into high-achieving educational environments.

And it’s a task that Johnson, former director of Student Achievement and School Accountability at the U.S. Department of Education, is facing one school at a time.

Demographics defining destiny

Fact: A black 8th grader in the United States is four times less likely to be proficient in mathematics than a white 8th grader. (Source: National Assessment of Educational Progress, “The Nation’s Report Card: 2005”)

Fact: A 4th grader who qualifies for a free- or reduced-price lunch program is two-and-a-half times less likely to be proficient in reading than a child who doesn’t meet income eligibility requirements. (Source: National Assessment of Educational Progress, “The Nation’s Report Card: 2005”)

“Too often demographics define destiny,” Johnson said. “All students of all groups need to be educated in a way that will encourage them to be high achievers and that is what NCUST is dedicated to help urban schools do.”

While race and low income levels represent the most significant risk factors that stifle student success, there are high-achieving urban schools. It begs the question: what are they doing to overcome the long odds dragging down most inner city schools across the country?

Lessons learned

Johnson hit the road to get some answers. He visited high-ranking urban schools across the country to see what novel initiatives they had developed that could be replicated in less successful inner city schools.

Johnson traveled to Muller Elementary School in Tampa, Fla. Despite 74 percent of its students living at or below the poverty level, Johnson said the school has created a successful academic environment, where students meet and exceed state test score requirements.

Principal Bonnye Taylor said Muller Elementary overcame long odds by creating an enjoyable learning environment and inspiring students.

“Our school-wide, theme-based curriculum is designed to motivate attendance,” Taylor said. “We get all the students involved and we make the units fun to learn, which translates into kids wanting to be here.”

Muller Elementary School is one of nine schools honored with NCUST’s Excellence in Education Award last year.

“The reason schools like Muller are so successful is because they have a relentless focus on getting their students to achieve at high levels,” Johnson said. “They assume all students have the ability to learn challenging material, even when they come from difficult or disadvantaged home situations.”

Empowering parents

Johnson visited Linwood Elementary School in Oklahoma City, Okla., which also received NCUST’s Excellence in Education Award.

Principal Kathy Draper said her school, which is at the center of the midwest city, has had success by making education a family affair.

Ninety-seven percent of Linwood’s students live at or below the poverty level. Many of the parents work multiple jobs that leave little time to help their children with schoolwork. Also, more than half the parents are Hispanic and don’t speak English fluently.

“We decided we needed to help get parents up to speed to improve their own lives and for the sake of their children,” Draper said.

Draper and her staff developed adult education courses to teach English to parents, while providing daycare for the kids so the parent could attend. The classes were so popular, Draper said they plan to expand their program next year to offer general education degrees and citizenship classes, as well.

“By empowering the parents to be more successful, we are creating a positive environment for their children and a better opportunity for the children to succeed,” Draper said.

The urban equation

Programs like these are taking urban schools to a new level, Johnson has discovered.

“NCUST is going out there, finding out what’s working in these inner cities and helping schools in urban environments nationwide to do the same,” Johnson said.

The development of a great urban school takes time, energy and resources. But with NCUST doing the legwork, Johnson hopes more schools will have the opportunity to succeed — even with deficiencies in those areas.

A grant proposal under consideration by the U.S. Department of Education would provide five City Heights schools with funding to integrate “best practices” discovered by Johnson and NCUST. The money would also pay to train new and aspiring administrators enrolled in SDSU’s education programs.

“We want to pilot a new way of leading,” Johnson said. “If we know the ways to make an urban school successful, we should be sharing that early on during preparation so educators and administrators get it right from the start.”

Johnson said that teachers, students, parents and administrators all play a part in transforming urban education. Successful schools truly engage their students and create an excitement for learning.

“Teachers work with parents in ways that build a stronger foundation for student learning,” Johnson said. “The schools that really succeed in turning themselves around continue to build on their best practices and work tirelessly to improve.”

Local solutions

Back in San Diego’s City Heights, Monroe Clark has struggled to escape the formidable challenges facing a school with virtually all its students at or below the poverty line.

“Families in poverty are a lot less stable,” said Principal Barbara Balser. “They move around a lot and they are stressed over their money situation, which leaves a lot less time and energy to focus on their children’s education.”

Balser said the administrators and staff resolutely believe in the NCUST program.

“We have a concrete game plan for improvement,” Balser said. “We know it will work and that helps us stay focused on our goals.”

Sources of support

A $14.5 million grant from Qualcomm was the driving force behind NCUST. It is just one of the initiatives supported by the Qualcomm Institute for Innovation and Educational Success. The institute also supports three other centers working to identify and address major issues critical to the long-term prosperity of the San Diego region.

- Project Lead the Way aims to attract and prepare future engineering majors by exposing engineering curriculum to students in middle school and high school. SDSU is also home to the training center for teachers participating in the program. For the past several years, teachers learn the hands-on curriculum in SDSU’s College of Engineering. They take those lessons back into their classrooms. Since the program was started in San Diego, 175 teachers have been trained and more than 1,800 students have taken Project Lead the Way courses every year.

- Improving Student Achievement in Mathematics (ISAM) was created to improve student understanding and achievement in mathematics by enhancing teaching methods in grades K – 12. ISAM programs offer K-12 math teachers the opportunity to re-examine their courses and gain a deeper understanding of instruction and the connections to other mathematical ideas and concepts. The program has multiyear partnerships with four local school districts: Sweetwater Union High School District, Ramona Unified School District, Lemon Grove School District and the City Heights Educational Collaborative.

- People, Information, Communication and Technology (pICT) is an interdisciplinary pilot program at SDSU designed to improve the use of technology in all areas of teaching. Faculty are provided introductory, intermediate and expert instruction to implement the latest technological tools into their curriculum.