Sea Squirt Offers Hope for Alzheimer's Sufferers

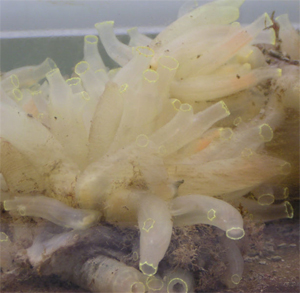

SDSU researchers say the sea squirt is a potential new resource for drug development.

Alzheimer’s disease affects an estimated 27 million people worldwide and is the most common form of age-related dementia. There is no cure, however, San Diego State researchers Mike Virata and Bob Zeller have found that the sea squirt may hold the key for developing more efficient drugs to target the disease.

Attacking buildup

One of the characteristic changes in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients is the buildup of plaques and tangles. Currently, the best hope for curing, or at least slowing, the disease lies in developing drugs that target this buildup.

However, a major obstacle in rapidly screening potentially useful drugs has been the lack of a good model system in which Alzheimer’s plaques and tangles appear quickly.

Modeling the disease

The sea squirt, the closest invertebrate relative to humans, shares about 80 percent of its genetic code with humans when in their immature, tadpole form. Researchers set out to see if it would be possible to model Alzheimer’s disease in the tiny animals, which share all the genes needed for the development of Alzheimer’s plaques in humans.

“Because of their small genome size, simple body plan organization and rapid development, sea squirts have long been recognized as an excellent model to study early developmental mechanisms,” said Zeller, SDSU biology professor.

“By adding the ability to examine simple genetically encoded behaviors, we’re hoping to establish sea squirts as a more direct model for human neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease."

Encouraging results

After dosing the tadpoles with a mutant protein found in human families with hereditary Alzheimer’s, researchers saw an aggressive development of plaques in the tadpoles’ brains in just one day. They were able to then reverse the development of plaques by treating them with an experimental anti-plaque forming drug.

This is an important breakthrough, as all other invertebrates that have been tested were unable to process the plaque-forming protein, and vertebrates take months or years to make plaques. The researchers’ exciting results make it a real possibility that sea squirts are an excellent model for testing new drugs in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease.

The study will be published in an upcoming issue of the research journal, Disease Models & Mechanisms (DMM).