NASA Finds New Planetary System

SDSU astronomy professors played a large part in analyzing data about new planets, including some Earth-size candidates.

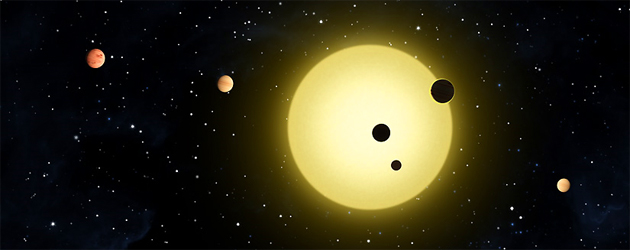

In May 2009, NASA’s Kepler Mission launched as the first mission capable of finding Earth-size planets around other stars. A year-and-a-half and 150,000 stars later, it announced its biggest discovery to date: the first Earth-size planet candidates; candidates that could potentially sustain life; and Kepler-11, a new planetary system containing six planets orbiting a sun-like star — the largest group yet discovered outside our solar system.

“The interesting thing is that we found a planetary system with six planets that were all eclipsing,” said Bill Welsh, SDSU astronomy professor and one of nine astronomers nationwide serving as a participating scientist for the mission. “This shows us that we’re going to find planetary systems, not just cases of one star with one planet circling it.”

Welsh, together with SDSU astronomy professor Jerome Orosz and former College of Sciences Dean Don Short, is among the team of scientists analyzing Kepler data around the clock. They played a large role in Kepler-11 by measuring various properties of the six planets, including their sizes and orbits.

Earth's distant neighbors

Kepler-11, located approximately 2,000 light-years from Earth, is the most tightly packed planetary system yet discovered. All of the planets in the system are larger than Earth, with the largest ones comparable in size to Uranus and Neptune.

The planets interact with each other gravitationally, which speeds up and slows down their orbits by about 10 minutes. This was essential in confirming that these were indeed planets.

“The fact that they influence each others’ orbits and have this gravitational interaction tells us that they’re planets, and not just background stars mimicking planets,” Welsh said.

All six of Kepler-11’s confirmed planets have orbits smaller than the orbit of Venus. The orbital period of the outermost planet is 118 days, around the size of Mercury’s.

Searching for planets

Kepler looks for planets by measuring tiny decreases in the brightness of stars caused by planets crossing in front of them.

“When a planet eclipses a star, there’s a very small percentage (around 0.1 percent) of the star’s light that is lost. This helps determine the size of a planet,” explained Orosz, whose main role was to measure planet size. “Once the size is known, the planet’s density can be figured out, which gives scientists an idea of what the planet is made of (e.g. water, rocky material or a mixture of the two).”

The planets discovered in Kepler-11 are fairly low-density planets, compared to Earth, and are more gaseous than rocky. They are also incredibly hot, with temperatures about 1,000 degrees.

Surveying the sky

The Kepler discoveries released by NASA on Feb. 2 include more than 1,200 planet candidates, 68 of which are Earth-size. Fifty-four planet candidates were found in the habitable zone, or area where life is most likely to exist. Five of those were near Earth-size (less than twice the size of Earth). Candidates pass rigorous tests, but still require follow-up observations to verify that they are actual planets.

The findings are based on the results of observations conducted May 12 to Sept. 17, 2009, of more than 150,000 stars in Kepler's field of view, which covers approximately 1/400 of the sky.

“The fact that we've found so many planet candidates in such a tiny fraction of the sky suggests there are countless planets orbiting sun-like stars in our galaxy,” said William Borucki of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., the mission's science principal investigator. “We went from zero to 68 Earth-sized planet candidates and zero to 54 candidates in the habitable zone, some of which could have moons with liquid water.”

The Kepler-11 findings were published in the Feb. 3 issue of the journal Nature.