Overconnectivity in Brain Found in Autism

Findings from SDSU's Brain Development Imaging Laboratory differ from current brain connectivity theories.

Although it has been long known that autism is primarily a neurological disorder, the exact nature of brain disorders in autism is not well understood. Two recent studies from San Diego State’s Brain Development Imaging Laboratory suggest that current theories may be missing an important piece of the picture: overconnectivity in the brain.

Recent evidence has suggested that brain connectivity is affected in those with autism, and many studies have reported “functional underconnectivity,” meaning that regions in different parts of the brain talk less to each other. The underconnectivity theory, which was originally proposed in 2004, received broad attention and has been generally accepted until recently.

About the SDSU studies

However, in a study led by SDSU psychology Professor Ralph-Axel Müller (published in Cerebral Cortex), all existing studies of functional connectivity were surveyed and it was found that a growing number of studies actually show a very different pattern of results, suggesting that in autism, the brain may be partly overconnected.

This hypothesis was then tested in a second study from the same lab, led by Patricia Shih and published in Biological Psychiatry. It found that a brain region in the temporal lobe, which is important for several functions known to be impaired in autism (biological motion perception, language, auditory processing, auditory-visual integration), is more widely connected with other parts of the brain in children and adolescents with autism than in typically developing children.

This study is also the first to show that the specialization of cortex in this part of the brain is reduced in those with autism. Whereas in typically developing children, neighboring parts of cortex become increasingly specialized with age, this specialization was found to be impaired in children with autism.

Different perspective of autism

These findings create a picture of brain abnormalities that differs strongly from the “underconnectivity theory.” The data suggest that functional networks in the brain, which specialize in different functions (e.g., language or imitation), are not simply less well connected. Instead, cognitive and behavioral problems in autism may arise from the fact that these networks connect broadly with too many other parts of the brain and therefore do not specialize well.

The causes of these impairments are not understood at present, but they may relate to findings of early brain overgrowth in children with autism. Impaired “synaptic pruning,” which refers to the loss of connection between nerve cells that is important for brain organization and network specialization in typical development, may also play a role in overconnectivity observed in the study by Shih and colleagues.

More about the illustration at the top of the story

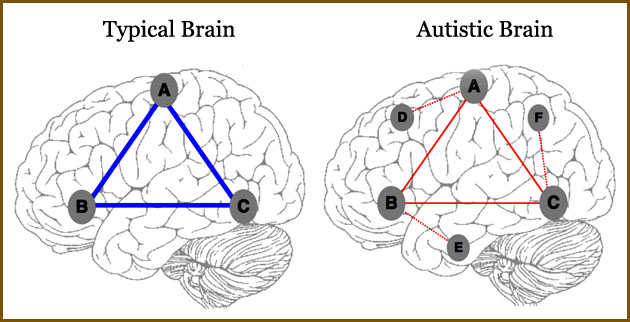

Illustration of atypical connectivity patterns observed using functional connectivity MRI. In the typical brain, a simplified example network shows strong connectivity (thick blue lines) between three brain regions (A, B, C).

These three regions are connected more weakly in ASD (thin red lines). However, the network also includes connections with other brain regions (D, E, F) that do not exist in the typical brain (dotted red lines).