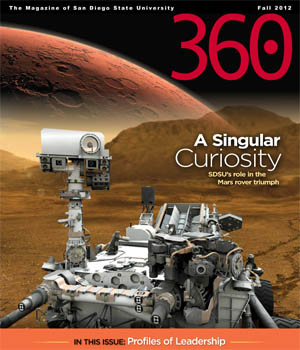

Engineering the Rover

SDSU alumni are part of the team that sent Curiosity to Mars.

Jordan Evans ’93 knows the Mars rover Curiosity as only a parent can know a child. He has marveled at its complexity and recognized its potential. It has kept him up late into the night.

At NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif., Evans spent six years of his life with the team that developed and equipped NASA’s fourth and most capable Mars rover. He was deputy flight systems manager, one of two engineers responsible for every piece of equipment the rover would carry into space.

See the complete fall 2012 issue of 360 Magazine

So in August, as Americans watched Curiosity’s spectacularly successful arrival on the red planet—proud to be part of a country that could accomplish such a feat—Evans felt a deep personal sense of accomplishment and relief.

The tricky descent and landing had been picture perfect. In the first weeks on Mars, Curiosity flawlessly accomplished every given task—from transmitting images, to firing lasers to steering itself around the planet’s dusty terrain.

Which may explain why Neil deGrasse Tyson, oft-cited astrophysicist and director of the Hayden Planetarium, said the mission’s “greatest achievement is not scientific but engineering.”

Don’t expect any pushback to Tyson’s assertion from Evans or the seven other San Diego State alumni who helped put Curiosity on Mars. Six of them have engineering degrees and the two science majors in the group also work as JPL engineers.

A complex mission

Curiosity is the fourth Mars rover engineered by JPL and by far the most technologically advanced. Its two-year mission—to determine whether the red planet is, or ever has been, habitable to microbial life—was fraught with challenges, including the notorious landing sequence employing a giant parachute, a rocket-controlled descent vehicle and a bungee-like apparatus JPL called a sky crane.

“People understood the operation was iffy,” said Mark Ryne ’80, an orbit determination analyst with the navigation team. “Even if we do everything right, a rock can tip it over. In our work, there are either spectacular successes or spectacular failures. If it’s a failure, they bring in grief counselors. It’s like losing a child.”

Amanda Thomas ‘97 remembers watching one of NASA’s failures on a black-and-white TV in her native Grenada. The Challenger space shuttle broke apart just after takeoff, killing all seven crew members. Despite the tragedy, Thomas was inspired. When her family later moved to Pasadena, she began imagining a career with JPL, just up the hill from her new home.

Today Thomas is a supervisor at the Deep Space Network Goldstone complex in the Mojave Desert, which provides a vital communications link between JPL and Curiosity. Part of the job, she said, is to wake Curiosity, establish a command link, collect its data and put it to sleep.

Laid-back feel

Located in the hills above the California Institute of Technology, JPL has the laid-back feel of a college campus. It is the only facility outsourced by NASA, and under the terms of the contract, all 5,000 staff are Caltech employees.

Doug Clark ’85 is the Curiosity mission veteran among the SDSU alumni. Seven years ago, he helped develop the interface between Curiosity’s science instruments and its electronics. Clark’s work enables the rover to complete its assignments and transmit data back to the Mars Science Lab in Pasadena. Since childhood, space exploration has fascinated him.

“I was in middle school when Viking landed on Mars,” Clark recalled. “Then came the Voyager grand tour (of Jupiter and Saturn). JPL was recruiting on the SDSU campus in my senior year, and I wasn’t going to turn them down.”

Clark joined the Curiosity team in 2005, the year Joey Brown and Brandon Florow graduated from SDSU. Brown and Florow had attracted some media attention, while still on campus, as engineers of an experimental liquid rocket, and the experience gave them a unique advantage.

“No other university was building a liquid rocket at that time,” Brown said. “When I showed that work to the people here at JPL, they were impressed.”

Dream jobs

Bonnie Theberge ’86 also joined JPL straight from SDSU, and is now supervisor of the Mars Science Lab Test Bed team. Her group assembled a life-sized, nearly exact replica of Curiosity and tested it “to get the bugs out” before the rover was launched last November. Tests continue on a daily basis before Curiosity undertakes each of its scientific tasks.

Theberge, whose parents are also SDSU alumni, calls her role at JPL a dream job, and understands why Americans are intrigued with the red planet.

“I think it has to do with Mars being the closest planet and the one people might actually visit someday,” she said. “My husband and teenage children watched the landing with me. To see their excitement brought tears to my eyes.”

Florow also admits to tearing up at Curiosity’s arrival in the Martian atmosphere.

The rover’s entry, descent and landing came to be known as the “seven minutes of terror” because of the brief time window available to slow the rover from 13,000 miles per hour to zero and winch it to the surface from a hovering rocket stage. The operation was so perfectly executed that JPL officials later renamed it “seven minutes of triumph.”

“To be working on something for six years and have that kind of perfect outcome,” Florow paused, “…it means we did our jobs. And now I can say that something I touched is on the surface of Mars.”

This summer, as Curiosity took its place in the annals of U.S. space history, seven SDSU alumni became national heroes for their part in nudging humanity just a little farther out along the final frontier.