From SDSU to Mars

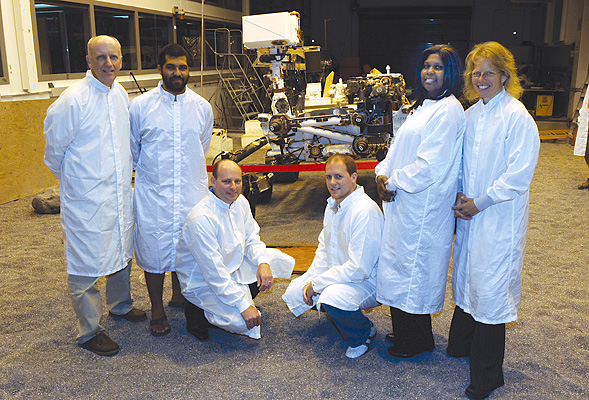

Aztecs from the Class of 1980 through the Class of 2005 were part of the Mars Science Laboratory team.

In early August, the Mars Rover "Curiosity" successfully landed in an effort to discover more about earth's next door neighbor.

Eight SDSU alumni who work with the Mars Science Laboratory played a variety of roles in the mission, from systems engineer to spacecraft navigator;

- Mark Ryne

- Doug Clark

- Bonnie Theberge

- Jordan Evans

- Amanda Jeremiah Thomas

- Brandon Florow and Joey Brown

- Dave Herman

Although he graduated with a degree in astronomy from SDSU, Mark Ryne, ’80, never thought he wanted to work at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL). A symposium changed his mind.

“I looked at the program and circled the papers that looked interesting. A JPL scientist wrote every one I circled. Shortly afterward, I applied for a job. That was late 1982, and I’ve been here ever since.”

Ryne is part of JPL’s navigation team. Simply put, he determines the location of a spacecraft and where it’s going. For the Curiosity mission, he was “surge” navigator—joining the team in the last few months before the Mars landing.

Over the years, Ryne has also worked on Phoenix, the first project in NASA’s program of scout missions to Mars; Deep Impact, which launched a space probe to collide with a comet 267 million miles away in order to study the comet’s composition; and the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL), designed to create the most accurate gravitational map of the moon to date.

“What we do at JPL is very public,” Ryne said. “It’s also dramatic, like a sporting event. A huge crowd is watching you. But what many people don’t appreciate is the complexity of the science and engineering required to get into space and work there.”

Other girls played with dolls; Bonnie Theberge preferred protractors and triangles. They were the tools of her engineer grandfather, Albert McKee, who built many of San Diego’s roads in the 1950s and ‘60s.

“By sharing his tools, my grandfather showed me a practical way to use the math and science skills I enjoyed and excelled in,” Theberge said.

The decision to attend SDSU was a no-brainer for Theberge and her sisters. Their parents, Robert and Patricia Chandler, were SDSU graduates and loyal supporters of Aztec Athletics. (Her dad was Padres broadcaster Bob Chandler.) Attending football and basketball games together was a family ritual.

Just out of SDSU with a degree in electrical engineering, Theberge landed her “dream job” at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL). She was assigned to the team responsible for testing equipment for the Magellan mission to Venus.

Now, she supervises testing for multiple projects.Her group assembled a replica of the rover to test it against hundreds of different scenarios before the launch. But the testing didn’t end with Curiosity’s landing in August.

“We still have test beds in place,” Theberge said. “Before JPL commands the rover to do anything, we test the replica in a simulated Mars yard here to get all the bugs out. Then we can be more confident of its success on the surface of Mars.”

Curiosity's first images of Mt. Sharp and the barren Martian landscape released a flood of childhood memories for Jordan Evans.

"I was captivated by space but it was Mars that really hooked me when Viking sent its images back to Earth in 1976."

Although Evans was not yet a teenager then, his fascination with Mars endured, eventually winning out over a deep love of music when it came time to choose a major at SDSU.

He chose aerospace engineering, but spent hours in the music building, rehearsing sousaphone with the marching band and electric bass with the pep band. Now an accomplished musician, he performs with big bands and small jazz ensembles in Southern California.

At NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab, Evans has led the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) team through the challenges of Curiosity's design, development, testing and operations on the surface of Mars.

He joined the mission as deputy flight system manager--responsible for the development of every piece of equipment strapped onto the rocket. Now he is engineering development and operations manager for the MSL as Curiosity goes about its two-year mission on the red planet.

For Evans, Curiosity's success is part of the continuum of space exploration. "We were standing on the shoulders of the Voyager team (which sent spacecraft as far out of our solar system and are still operating today) and many others that came before us, but we tried to expand the technology in every aspect of the project."

Amanda Jeremiah Thomas can tell you it’s a long way from the small Caribbean island of Grenada to the Mojave Desert, and an even longer road from aspiring secretary to supervisor at NASA’s Deep Space Network.

Thomas was 15 when her parents moved the family from Grenada to Pasadena, Calif., close to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab. She hoped to work there, but college wasn’t an option despite good grades. Her family couldn’t afford it.

Thomas aimed for a secretarial job until a high school counselor planted the seeds of possibility. “I realized that going to college for aerospace engineering could get me into JPL,” Thomas said, “and that’s how I found SDSU.”

As a freshman, Thomas had trouble adapting to the rigor of higher education. A “kind” upperclassman volunteered to tutor her. They lost touch when he graduated, but two decades later, Thomas saw his name in a story celebrating the successful landing of Curiosity on Mars. It was Jordan Evans, ’93, deputy flight systems manager for the mission.

Although Evans and Thomas work in different JPL facilities, both are involved in Curiosity’s complex mission. The Deep Space Network, where Thomas is supervisor, provides the vital two-way link between Earth and the rover, waking Curiosity, establishing a command link, collecting the data it gathers and putting it back to sleep.

Brandon Florow and Joey Brown '05

Brandon Florow and Joey Brown have been friends since their student days at SDSU. Both aerospace engineering majors, they were part of a student-run project to build a liquid-fueled rocket in 2004-2005.

It’s no coincidence that the experience landed them jobs at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) and roles in the development of the Mars Science Laboratory’s rover Curiosity. Only one other university had a liquid-fueled rocket project operating at the time.

Today, Florow is a mechanical systems engineer at JPL, and worked on a variety of tasks for MSL. His main job was as the close clearance engineer, responsible for ensuring that no part of the rover collided with any other part during Curiosity’s launch, entry into Mars’ atmosphere, landing, and operations on the surface.

For months before the launch, he used models and simulations to test for possible flaws, and made hundreds of measurements of the hardware. The team redesigned those parts of the rover that failed the tests.

Brown joined Curiosity’s entry, descent and landing team to work on the rover’s landing radar. His role was to ensure that the vehicle’s radar would “see” the surface of Mars after separating from the heat shell, thus triggering the sequence that allowed Curiosity to separate from the backpack, engage with the sky crane and be lowered to the surface.

Said Brown: “I spent many months out in the desert, testing and testing that radar to make darned sure it was going to see the ground and get us to the surface of Mars.”