Catching the Right Critters

New analysis reveals the complex and interconnected nature of the accidental capture of marine megafauna across the world.

Whenever fishing vessels harvest fish, other animals can be accidentally caught or entangled in fishing gear as bycatch. Numerous strategies exist to prevent bycatch, but data have been lacking on the global scale of this issue. A new in-depth analysis of global bycatch data provides fisheries and the conservation community with the best information yet to help mitigate the ecological damage of bycatch and helps identify where mitigation measures are most needed.

“When we talk about fisheries’ catch, we’re talking about what fishers are aiming to catch,” explained Rebecca Lewison, an ecology professor at San Diego State University’s Coastal Marine Institute Laboratory, who led the study with biology professor Larry Crowder of Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station and Center for Ocean Solutions. “Bycatch are the animals they don’t want or mean to catch.”

Bycatch may include seabirds, sea turtles and marine mammals. When these animals are accidentally tangled up in fishing lines or nets, nobody wins. It not only harms the local ecological balance, it also damages fishing gear and costs the industry time and money.

Bycatch mitigation

While this new analysis illustrates that bycatch is a complex, global process, the good news is that several strategies already exist to prevent bycatch, many of them developed by the fishing industry. For example, by varying the depth at which lines and nets are deployed, by using specially designed lures and hooks, and by employing turtle excluder devices, fisheries have increased target catch and reduced bycatch.

“Some of the earliest bycatch issues involved marine mammals taken in tuna nets and shrimp trawls that drowned sea turtles,” Crowder said. “The problems were ultimately solved by scientists who clearly defined the problems and by managers and fishermen who sought innovative fishing methods to allow fisheries and protected species to coexist.”

In the past, much of the research done in this area focused on specific species or on specific fleets. While those snapshots have been important and useful, Lewison said, they’ve missed the larger, integrated picture.

“If you’re a turtle, you probably don’t care about what country, or what type of gear or which fleet catches you,” Lewison said. “You just care that you got caught.”

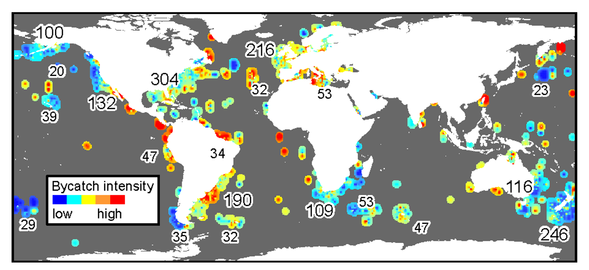

Looking globally

That’s the attitude Lewison and her colleagues applied to their latest study, published March 17 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. As part of a research initiative funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the scientists looked at hundreds of peer-reviewed studies, reports and symposia proceedings published between 1990 and 2008 to obtain a global perspective on what kinds of animals were being caught, where they were being caught, and the types of gear in which they were trapped. The researchers then compiled all of this information into a single comprehensive map and dataset.

“We call this the whole enchilada,” Lewison said. “It highlights the importance of looking at the bycatch issue across different species, fishing gears and countries. When you do that, it is clear that to address bycatch, fishing nations need to work together to report and mitigate bycatch. No single country can fix this. “

The study also revealed gaps in the available bycatch data, such as the lack of information on small-scale and coastal fisheries and from many ocean regions that are heavily fished by commercial fleets.

“Industry has taken the lead in developing mitigation in many countries, but these measures aren’t used everywhere,” Crowder said. “The fact is that as long as we have a fishing industry, we’re going to have an ecological footprint. We need to use the best-available data, science and technology to reduce that footprint as much as we can.”