Is Southeastern San Diego's Food Desert a Mirage?

SDSU geographers analyzed the food landscape of Southeastern San Diego and found reasons for optimism.

When San Diego State geographers Pascale Joassart-Marcelli and Fernando Bosco were tasked with looking into Southeastern San Diego’s food landscape, they mostly expected it to live up to its reputation as a “food desert,” with a dearth of fresh, affordable healthy food options.

“When we began this project, we knew that Southeastern San Diego was a low-income community and we had heard so many stories about the food environment that we were expecting the worst,” Joassart-Marcelli said.

Once they dug deeper, they realized the reality was much more complex.

“Yes, we found convenience stores packed with nothing but junk food and liquor stores where a handful of lemons was the only fresh produce available,” she said. “But we also discovered a few unassuming shops busy with local customers choosing from a variety of fresh fruits and vegetables, and a vibrant community trying to improve access to fresh and healthy food.”

Although Southeastern San Diego has been classified by the USDA as a food desert, that appellation does not accurately reflect the neighborhood's food landscape according to a new report headed by Joassart-Marcelli and Bosco. In Southeastern San Diego, as in many low-income urban communities, there are many sources of food that are ignored by studies that only focus on access to traditional supermarkets.

“The important question is whether these other food retailers—the discount stores, corner shops, ethnic markets, fast food restaurants and liquor stores—provide food that is healthy, affordable and culturally appropriate,” Joassart-Marcelli said. “And if they are not, we need to develop ways to encourage these smaller retailers as well as local entrepreneurs and growers to provide healthier options instead of always turning our attention to large supermarket chains.”

Food and place

Last year, Joassart-Marcelli and Bosco were awarded a three-year grant from the National Science Foundation to study the economic, political, cultural, and emotional relationships between food, ethnicity and place in three culturally diverse neighborhoods in San Diego.

This most recent report emphasizes the challenges and health risks posed by the current food landscape, while at the same time drawing attention to local resources and ongoing initiatives that present opportunities for building a healthy, sustainable and fair food environment. Many such efforts have been spearheaded by Project New Village, a partner on the study and a grassroots organization working actively in Southeastern San Diego to promote food justice.

The labels used to describe a community can influence the perceptions and responses of both its residents and people outside it, Bosco argues. “’Food desert’ can be a stigma that begs for outside intervention, which may not necessarily be what is most needed,” he said

The study’s authors suggest that “food swamp” may be a more accurate designation.

“Healthy food is sometimes there, but not always where you would expect it and typically in limited variety,” Bosco said. “Often it is overshadowed by high-calorie and low-nutrient food, which is much more readily available and convenient.”

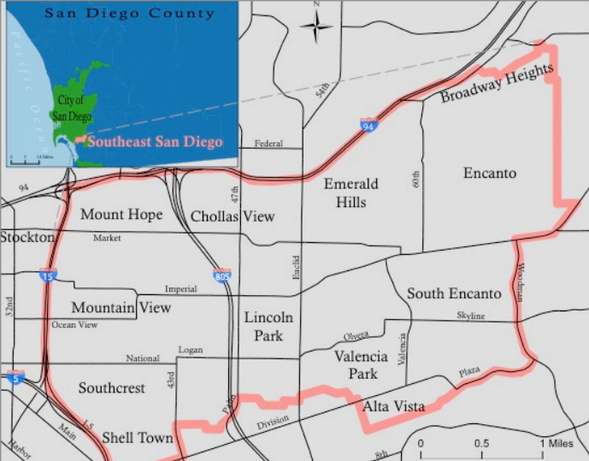

To better catalog the availability of a variety of foods, Joassart-Marcelli and Bosco worked with undergraduate students to audit stores and restaurants in the area. Last fall, faculty and students canvassed the neighborhood (roughly bounded by Interstate 15 to the west, State Route 94 to the north, Division Street to the South, and Encanto Park to the east) and collected detailed data on the cost, diversity, and quality of food.

“Our goal was to move beyond traditional measures of food access that only take into account big-box retailers” Bosco said. “Collecting these data was time-consuming, but it gave us a much more nuanced and richer picture of the neighborhood’s food environment.”

Swamp, not desert

In contrast to a typical food desert, what the researchers found was a combination of challenges and opportunities. Among the challenges:

- Many residents in the area live in poverty and have limited mobility.

- There are more fast food restaurants in the area than fresh produce retailers.

- Access to food stores, especially those selling fresh produce, is limited in the eastern part of the area.

- Many stores that did carry fruits and vegetables did not have much variety.

- In contrast, “junk food” such as candies, cookies, chips, sodas and energy drinks were disproportionately available in all stores.

- Retail prices were higher for most items, especially highly perishable foods.

Yet, the researchers also saw opportunities for improvement in the community. “The local purchasing power in low-income neighborhoods is usually underestimated,” Joassart-Marcelli said. There is a virtually untapped market for healthy food that could greatly benefit the neighborhood’s businesses and residents, Joassart-Marcelli and Bosco suggest.

They believe that with the right incentives and training, local shops could bring in healthier options, potentially creating outlets for local growers and food entrepreneurs.

Southeastern San Diego’s historical tradition of farming, which has been lost in recent years, could also make a rebound. The community’s increasing involvement in growers’ groups, community gardening, and a weekly farmers’ market, under the leadership of local organizations, seem to indicate that this trend is reversing.

The new report, “Southeastern San Diego’s Food Landscape: Challenges and Opportunities” will be publically released April 11 at the Cesar E. Chavez Community Tribute and Event hosted by Project New Village at the Educational Cultural Complex (4343 Ocean View Blvd., San Diego, CA 92113) from 5 to 8 p.m. Joassart-Marcelli and Bosco will introduce the report, then turn to civic and community leaders to hear their suggestions for improving Southeastern San Diego's food landscape and San Diego’s food system as a whole.

In the coming months, Joassart and Bosco will compare the conditions in Southeastern San Diego with those of other neighborhoods, including City Heights and Little Italy. The next phase of the study will be an ethnographic study investigating how children and families navigate their local food environments.

The full report and executive summary, as well as information about the Food, Ethnicity and Place project can be found here.