A Stem Cell Link Between Coxsackie Virus and Heart Disease?

A new study by SDSU biologists has found that coxsackie virus infects cardiac progenitor cells, potentially setting up infected hearts for early failure.

Scientists have known for years that there appears to be some connection between coxsackie virus and heart disease. Epidemiological evidence has shown that people who experience heart failure are highly likely to show signs of a previous infection by the relatively common type B coxsackie virus. Yet, exactly how coxsackie virus affects heart health has eluded researchers. In a new study published today in PLOS Pathogens, researchers at San Diego State University suggest a novel, promising explanation: A coxsackie infection depletes stem cells in the heart, eventually making it difficult for older hearts to handle stress.

Coxsackie infects approximately 2.5 million people in the United States each year, about 10 percent of those are newborns. The symptoms vary, but can include fever, gastrointestinal problems, muscle and chest pain, and rarely heart and brain inflammation. As many as half the people infected display no symptoms at all.

Previous research has found that between 70 and 80 percent of patients with heart disease were at one point infected with type B coxsackie virus, despite having no history of viral heart disease.

Targeting stem cells

In the study, led by SDSU molecular biologist Ralph Feuer and former SDSU heart researcher Roberta Gottlieb, now at Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute in Los Angeles, the researchers turned to mouse models to investigate the link between coxsackie and heart failure. Both experts in stem cells, they had a hunch that the virus might be undercutting the organ’s ability to repair itself.

Gottlieb previously published studies showing that juvenile exposure to the chemotherapeutic drug doxoxrubicin decreased the number of cardiac progenitor cells in the adult heart and produced similar heart failure symptoms in mice. Cardiac progenitor cells are similar to stem cells in their ability to turn into specific type of cells found in the heart, although their ability to self-renew is limited.

“We wondered whether a virus that targeted cardiac progenitor cells might have the same kinds of effects,” Feuer said.

In experiments led by Jon Sin, a recent doctoral graduate from the SDSU’s cell and molecular biology program and currently a postdoctoral researcher in Gottlieb’s lab, the researchers discovered that mice infected with coxsackie virus shortly after birth weren’t any more likely to develop heart disease through their youth into adulthood. As they grew older, however, they became much more likely to suffer heart failure than control mice in response to stress.

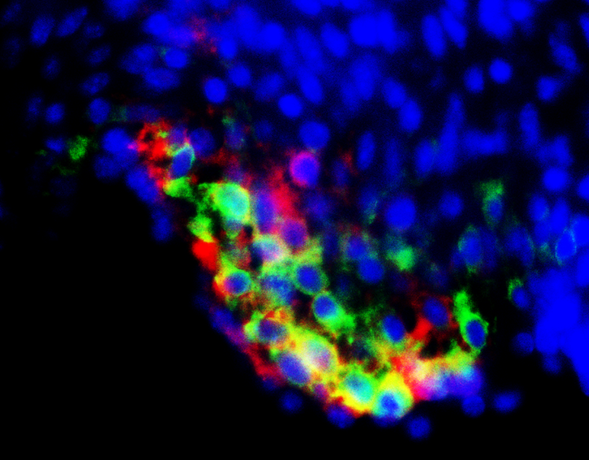

Looking more closely at the mice, the researchers found that the virus was indeed found in cardiac progenitor cells, and that as infected mice grew older, the number of progenitor cells dropped off significantly compared to control mice.

Stress test

Next, Feuer, Gottlieb and Sin tested to see whether they could detect the effects of this depletion of progenitor cells in adult mice by subjecting them to two different kinds of stressors: One group of mice infected with coxsackie virus was also given a drug that overstimulates the heart; another was vigorously exercised every day for two weeks.

A control group of mice showed no increased evidence of heart disease, but the coxsackie-infected mice showed clear signs of heart disease.

“That’s when we saw the disease process take place,” Feuer said. “The hearts looked normal, but when they underwent stress, we saw the consequences of the previous infection.”

After these experiments, the researchers examined the hearts of the infected mice and found that their hearts showed signs of not being able to rearrange and grow new blood vessels. As hearts are exposed to stress, such vascular remodeling is critical to their health, Feuer explained. The process is facilitated by progenitor cells; hearts with fewer progenitor cells might indeed have a more difficult time responding to stress.

Further studies will be needed before researchers know for sure whether these results extrapolate to humans, but Feuer is confident that this research provides new clues to the link between coxsackie virus and heart disease. Eventually, he hopes the work might lead to the administration of antiviral medicine that can fight off coxsackie virus during critical periods of development. The Feuer and Gottlieb laboratory are actively pursuing the development of novel antiviral therapies and vaccines against coxsackie virus, since so few options currently exist for infected patients.

Heart hub

San Diego State University is a hub for heart research, specifically research into cardiac stem cells. The Donald P. Shiley BioScience Center and the SDSU Heart Institute each have made several advances in the field of heart stem cells. Last year, Heart Institute key investigator Mark Sussman received an $8.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to explore the regenerative medicine possibilities of cardiac stem cells. Sussman was a scientific contributor to this study.