Brain Connections in Autism

SDSU researchers find more sensorimotor connections in the cerebellum, but fewer connections for higher cognition.

“If a particular part of the brain is already functionally active in one domain, there may be no reason for the brain to switch it over to another domain later in life.”

In early childhood, the neurons inside children’s developing brains form connections between various regions of brain “real estate.” As described in a paper published last week in the journal Biological Psychiatry, cognitive neuroscientists at San Diego State University found that in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder, the connections between the cerebral cortex and the cerebellum appear to be overdeveloped in sensorimotor regions of the brain. This overdevelopment appears to muscle in on brain “real estate” that in typically developing children is more densely occupied by connections that serve higher cognitive functioning.

The study represents the first ever systematic look at connections between the entire cerebral cortex and the cerebellum using fMRI brain imaging, and its findings provide another piece in the puzzle that could one day lead researchers to develop a reliable brain-based test for identifying autism.

Back to the cerebellum

Several decades ago, scientists reported findings that certain regions of the cerebellum—a brain region involved in motor control, but also in cognitive, social, and emotional functions—were often smaller in people with autism than in typically developing people.

That sparked a brief flurry of research activity exploring the cerebellum’s potential role in the disorder. Unfortunately, the direction never truly panned out for researchers hoping for a big breakthrough in understanding, said the study’s corresponding author, SDSU psychologist Ralph-Axel Müller.

“Eventually, interest in the cerebellum waned due to a lack of consistency in the findings,” he said.

Hoping that advances in brain imaging technology would reveal new insights, Müller, working with the study’s first author Amanda Khan, looked back to the cerebellum for their study. Khan is a former master’s student at SDSU and now a doctoral candidate at Suffolk University in Boston.

Over- and underconnected

The researchers directed 56 children and adolescents, half with autism and half without the disorder, to fixate on a focal point while thinking about nothing in particular, using fMRI brain imaging technology to scan the children’s brains as they produced spontaneous brain activity. Capturing this spontaneous activity is crucial to honing in on what are essentially baseline neuronal patterns.

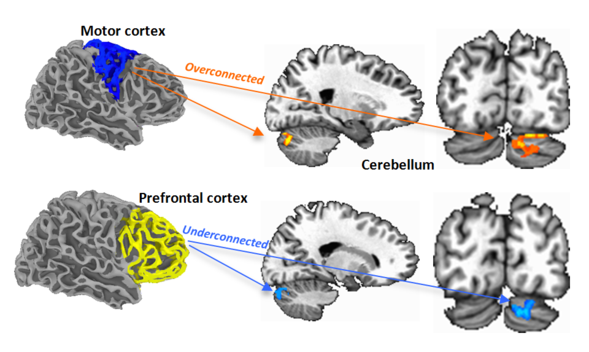

The imaging results revealed that the participants with autism had far stronger neuronal connectivity between sensorimotor regions of the cerebellum and cerebral cortex than did their counterparts without autism. Conversely, the participants with autism had less connectivity between regions involved in higher-order cognitive functions such as decision-making, attention and language.

The sensorimotor connections between the cerebral cortex and cerebellum mature during the first few years of life, when the brains of children with autism grow larger in volume than typically developing children, Müller explained. Connections that serve higher cognitive functions develop later, after this period of overgrowth.

“Our findings suggest that the early developing sensorimotor connections are highly represented in the cerebellum at the expense of higher cognitive functions in children with autism,” he said. “By the time the higher cognitive functions begin to come online, many of the connections are already specialized. If a particular part of the brain is already functionally active in one domain, there may be no reason for the brain to switch it over to another domain later in life.”

Neural neighborhood

Returning to the real estate metaphor, it’s as if most of the available land has already been scooped up by sensorimotor connections before the higher-order cognitive function connections have a chance to move into the neighborhood.

The findings could help scientists and clinicians better understand exactly how abnormalities during brain development lead to various types of autism spectrum disorder. Müller hopes his work will not only contribute to a brain-based diagnosis of autism, but also be a step towards identifying its various subtypes and underlying genetic factors.

“We still don’t understand what in the brain makes a kid autistic,” he said. “You can’t look at a scan and say, ‘There it is.’ We’re doing the groundwork of finding brain variables that might be biomarkers for autism and its subtypes.”

SDSU graduate students Aarti Nair and Christopher Keown, also contributed to the study, as did University of California, San Diego, graduate student Michael Datko and Alliant International University psychologist Alan Lincoln.