He's Chill

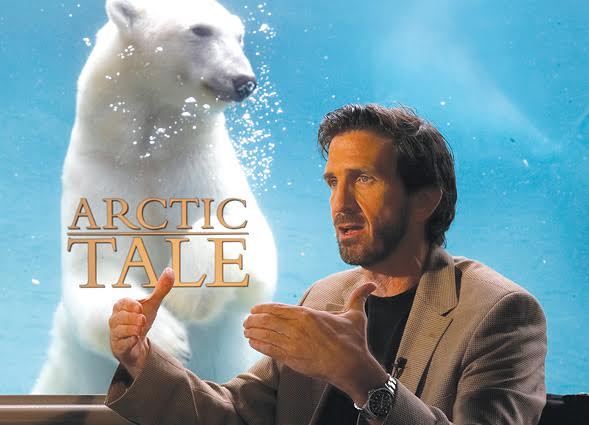

Adam Ravetch, '84, documents a world few others have seen.

This story appears in the fall 2015 issue of 360: The Magazine of San Diego State University.

Before he filmed bowhead whales mating, before he worked alongside scientists to attach cameras to polar bears, even before he made his first ice dive into the Arctic’s frigid depths, Adam Ravetch, ’84, was fascinated with narwhals.

These legendary whales, sometimes called unicorns of the sea, grow spiral tusks exceeding eight feet in length and can weigh up to two tons. Ravetch, a zoology major, had never encountered the word narwhal until he saw it on the license plate of Mark Flahan, San Diego State University’s diving safety instructor.

Flahan was a mentor to Ravetch in the world of sport diving and spear fishing, which originated in 1930s San Diego with a group of men who called themselves Bottom Scratchers. Some say the name describes their practice of grazing the ocean floor for fish.

On summer evenings, San Diego families would gather to watch the Bottom Scratchers return to shore, hauling 10-foot, hand-fashioned spears and their day’s catch. Hearing of their remarkable feats, Ravetch, too, was hooked—he wanted a piece of that briny world.

After graduation, he drove up the coast to California State University, Long Beach. Ravetch sought out pioneering researcher Donald Nelson, the first to document the agonistic displays of gray reef shark—behaviors they exhibit before an attack. Nelson was the media’s favorite shark expert, and Ravetch assisted the production crews that came to interview his advisor.

Arctic efficiency

Even then, he was drawn to the world of cinematography. In 1985, as a winner of the Our World Underwater scholarship, Ravetch globetrotted for a year, working with leading marine scientists, conservationists and cinematographers. Afterwards, he teamed up with Canadian filmmaker John Stoneman, protagonist of the wildlife documentary series, “The Last Frontier.”

“John first led me to the ice in the Gulf of St. Lawrence,” Ravetch recalled. “We dove underneath, and hundreds of seals were flying all around us. I was mesmerized. Every year since then, I’ve gone back to film in the Arctic.”

A typical expedition lasts four to six weeks, braving temperatures of 30 degrees below zero. Ravetch said he prefers the frigid climate to the tropical.

“Your food doesn’t spoil. You make fresh water by melting snow and you can build an igloo so you don’t have to carry a tent. There’s efficiency to operating in the Arctic. You just have to figure out how to keep your cameras from freezing.”

Ravetch’s cameras have captured wildlife behavior for many of the most respected natural history series, including Frozen Planet, Planet Earth and National Geographic’s Great Migration, for which he won an Emmy for cinematography.

He also co-directed and compiled more than 800 hours of footage for the 2007 documentary “Arctic Tale,” narrated by Queen Latifah. The film documents young polar bears and walruses as they experience the effects of gradually melting ice caps.

“When you’re there, side-by-side with the animals, that’s when it becomes intimate, that’s when you witness their intelligence and the decision-making processes they use to survive,” Ravetch said.

Secret nuggets

With each project, the goal is to document a behavior never before seen on camera. Ravetch describes it as “the secret nugget that keeps you coming back.” This fall, the nugget was footage of the mating rituals of bowhead whales, which, unlike most others of the species, spend their entire lives in Arctic waters.

Ravetch’s 25-year career has expanded the frontiers of scientific knowledge about inhabitants of the Arctic. For years, he dreamed of putting cameras on polar bears to document how animals behave when humans aren’t around.

The dream is now a reality. Ravetch has worked with scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey and the Canadian Wildlife Service to gather more than 500 hours of footage recorded by the bears themselves.

He also founded the Arctic Exploration Fund (AEF), a nonprofit dedicated to outfitting wild animals around the globe with cameras in order to document their behaviors and uncover the mysteries of their world.

For his next act, Ravetch intends to return, in a sense, to the origin of his fascination with the oceans. Look for his documentary on the narwhal—coming to theatres soon.