Fishing for Answers about Chinese Abalone

Archaeologist Todd Braje recently published a new book about a historic immigrant-run industry that met an untimely end.

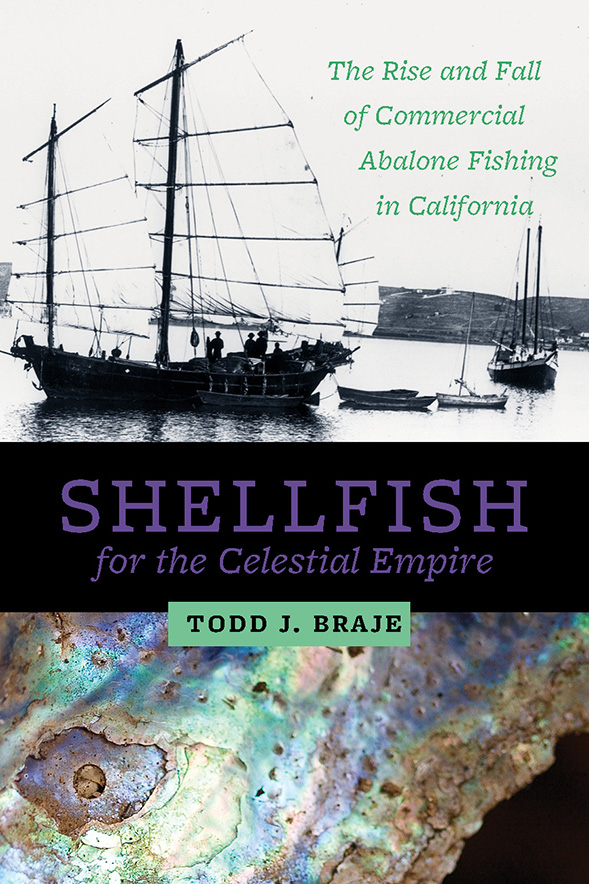

And last month, he published a book, “Shellfish for the Celestial Empire: The Rise and Fall of Commercial Abalone Fishing in California." The book explores the state’s once-booming mollusk-harvesting industry run by Chinese immigrants, as well as its demise at the hands of targeted U.S. and state legislation. Ecological collapse and overharvesting followed as the industry was flooded with non-immigrants, providing lessons for modern industries.

SDSU NewsCenter asked Braje to talk about what inspired him to write the book and what lessons can be drawn from this history.

What inspired the book?

I first became interested in abalone fishing sites when I was working on my Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Oregon, around 2005 and 2006. I was conducting archaeological excavations around San Miguel Island, one of the Northern Channel Islands, to build a 10,000-year-long record of human-environmental dynamics. I had this great sequence of Native American history, as well as the history of the islands starting in the latter half of the 19th century, but I realized I was missing the interval from about A.D. 1820—when the Chumash, the Native American inhabitants, left or were removed from the islands—until the beginning of the ranching period when the islands became privately owned. These Chinese abalone fishing sites were the critical missing piece.

Describe the research process.

There is a massive amount of academic and popular literature available on the history of 19th-century Chinese immigration to the United States and, in particular, to California during the Gold Rush. Following this literature, I discovered research on the history of 19th-century immigrant Chinese fisheries, particularly in California. What was largely missing was how Chinese immigrants started the first commercial shellfishery in California, fishing for black abalone (a type of large sea snail). One of my recent graduate students, Linda Bentz, did an amazing thesis project on this topic. She helped me compile all the historical documents, newspapers, catch records, census accounts, etc., that mentioned this industry. The historical records are spotty and lack detail, but they are fairly robust when you start pulling it all together.

I spent about eight years going to all the Northern Channel Islands and systematically recording, mapping, and sampling these sites. I brought dozens of different students into the field. It became a massive project and a really successful one that opened my eyes to this largely unrecorded history.

Did you meet any interesting people during this time?

I have met former commercial abalone fishermen and talked to them about their experiences. I have discussed research with Chinese history scholars. I have talked to descendants of Chinese abalone fishermen. Even just talking to folks who remember how cheap and readily available abalone was in California when they were young has been really interesting. The story of the rise and fall of abalone fishing in California is one that has affected a lot of people and resonates strongly.

What halted this industry?

The legislative actions that ended Chinese abalone fishing in California grew out of a larger anti-Chinese movement in the state and throughout the United States. By the 1870s, America slid into a severe economic depression, prompted by the finishing of the transcontinental railroad and the ending of the Civil War. The railroad was supposed to be a boom for the West, but cheap manufactured goods flooded the West Coast and new factories in California could not compete with the established sweatshops, mills, and factories of the East Coast. As has happened many times in U.S. history, people targeted recent immigrants as scapegoats. The Chinese were blamed for the nation’s economic woes and were seen as a hostile threat to the “American working man.”

Fishing taxes and license fees were passed, designed to target Chinese and other Asian groups. The financial burden became too much for many Chinese abalone fishermen, and they left the industry. The ugliest piece of legislation, however, was the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 by the U.S. legislature. This act excluded skilled and unskilled Chinese laborers from entering the United States and wasn’t repealed until 1943. I think remembering this ugly history and the lessons we should have learned from it are more important now than ever.

How does this story fit into the larger narrative of Chinese immigrants in America?

The story of Chinese abalone fishing in California is not only a microcosm for the 19th- and 20th-century Chinese immigrant experience but also, more broadly, that of many immigrant groups. Chinese abalone fishermen used the knowledge and skills they brought with them from China to take advantage of the untapped potential of California's coastal resources. Despite facing tremendous obstacles and racism, they founded a multi-million dollar shellfishery and helped shape the identity of our nation. But, like many marginalized groups, their contributions have been relegated to a footnote in U.S. and California history.

What lessons can we draw from this history?

I discovered in the course of my research that during the Chinese harvest the fishery was relatively sustainable—these fishermen went to great lengths to harvest abalone in a sustainable fashion. After they were legislated out of the industry and the fishery opened up to more and more fishermen, sustainable harvest strategies disappeared and abalone became massively overexploited. The ensuing story of ecological dysfunction, overharvesting, and eventual collapse is one that can be told about countless commercial fisheries worldwide. The lessons of history, the strategies employed by Chinese and Native American fishermen in California, can help us restore degraded ecosystems and better manage our marine and coastal fisheries into the future.