Celebrating 120 Years of SDSU Science and Research

For a dozen decades, the universitys faculty and students have exceeded expectations.

The seeds of San Diego State University’s current success in science and research were planted in the school’s earliest days. Its first incarnation—a teacher-training institution known as the San Diego Normal School—counted several Ph.D.-holding scientists among its faculty, who carried on research while preparing San Diego’s future teachers. This was extraordinary, writes SDSU anthropologist Seth Mallios in his book “Hail Montezuma!” as few normal schools in the country made a point of hiring faculty with Ph.D.s, let alone professors with active research programs.

Over time, professors began involving students in their research. A geology professor in the 1930s named Baylor Brooks took his students out to learn fieldwork techniques in the then-unpopulated hills and canyons surrounding campus. (A pair of rock hammers used in these field classes resides in SDSU’s Special Collections and University Archives.)

In the 1950s, a couple decades after the San Diego Normal School had transitioned to San Diego State College (SDSC), President Malcolm A. Love instituted a hiring policy requiring that all new SDSC faculty members have a doctorate degree, or be within a year of finishing one. That was a first-of-its-kind requirement for a California state college, and it resulted in more than half the college’s professors holding a Ph.D. At the time, there were more doctorate-holding professors at San Diego State College than at some established, research-oriented schools like the University of Oregon or the University of Arizona, Mallios wrote.

The first chair of the SDSC chemistry department, Ambrose “Amby” Nichols, was one of the earliest SDSC faculty members to receive a major research award. An alumnus of the Manhattan Project that had helped develop the atomic bomb, Nichols received funding from the Atomic Energy Commission between 1935 and 1955 to carry out his research into the properties of chemical compounds like phosgene and manganese. Nichols would eventually leave to become the first president of Sonoma State University.

By the end of the 1950s, SDSC offered 30 master’s degree programs and boasted a robust, well-funded research program in several disciplines including chemistry, physics, psychology, biology and mathematics. The college’s growing reputation as a destination for scholarly research was partially stymied in 1960, when the State of California passed the Donohoe Act, creating a tiered system for the state’s institutes of higher education.

The ability to independently offer Ph.D. degrees was reserved for the University of California system, while the California State College system was limited to awarding such degrees only jointly with a higher-tier institution. While the state legislature may have intended for San Diego State College to limit its ambitions to teaching at the undergraduate level, SDSC officials and faculty had grander ideas. President Love stated, “Our primary aim is teaching, but research is concomitant.”

SDSC partnered with the University of California, San Diego, in 1967 to confer the college’s first Ph.D., in chemistry, to SDSC professor Robert P. Metzger, who remains a professor emeritus at SDSU. Metzger said that President Love was “the single most important figure in upgrading San Diego State College to San Diego State University by fighting to establish the joint-doctoral program.”

Indeed, five years later in 1972, with the induction of President Brage Golding, SDSC became California State University, San Diego, then San Diego State University two years after.

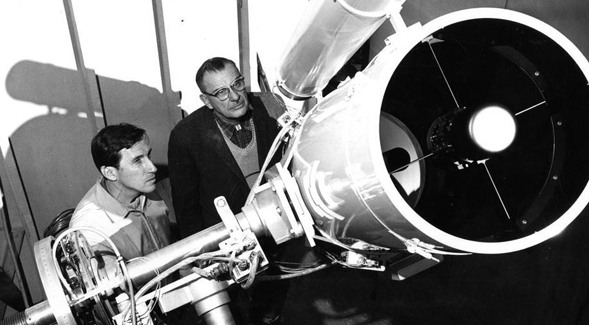

Around this time, SDSU was also establishing itself as a regional powerhouse in astronomy research. It opened the Mount Laguna Observatory (MLO) in 1968, funded by the National Science Foundation and led by SDSU emeritus professor of astronomy Ron Angione. Today, the observatory is regarded as one of the top dark-sky destinations in the Southwest United States.

Another high-water mark for the university’s research also occurred when SDSU graduate Ellen Ochoa (’80) became the first Hispanic woman to travel to space in 1993 aboard the shuttle Discovery. She helped to conduct a variety of on-board experiments.

Three years after Ochoa graduated from SDSU in 1983, SDSU biologist Sanford Bernstein joined the university and immediately received his first grant from the National Institutes of Health to study muscle degeneration in fruit flies. Thirty-four years later, he’s still working off the same grant—having been renewed eight times—making his one of the longest running NIH grants in the federal institution’s history.

Throughout the 1980s and ‘90s, SDSU’s research portfolio continued to grow. The university added joint doctoral programs in clinical psychology, education, biology, ecology, public health, electrical and computer engineering, mechanical and aerospace engineering, audiology and more. From 2006 to 2010, SDSU ranked first in the nation in research productivity among schools offering fewer than 15 doctoral programs.

In 2011, it outgrew the “small research university,” officially earning the classification of “research university” from the Carnegie Foundation. That same year, SDSU astronomers William Welsh and Jerome Orosz discovered the first definitive example of a planet that orbits two suns, Kepler-16b.

As SDSU closes out its 12th decade of existence, it continues to aim for the stars. The new Engineering and Interdisciplinary Sciences (EIS) Complex will open this January, creating space designed to inspire disparate scientific disciplines to find common ground and work together to solve global issues. In the new halls of EIS and the older ones surrounding it on campus, SDSU’s faculty, staff and students will continue to exceed expectations, training the bright young thinkers of tomorrow while contributing bold new ideas today.