SDSU Scientists Find New Way to Study Aggressive Form of Cancer

A persistent graduate student and fellow researchers have created a blueprint for scientists to study a cancer mutation in animal models.

Student scientists at San Diego State University have discovered a new way to investigate aggressive forms of cancer.

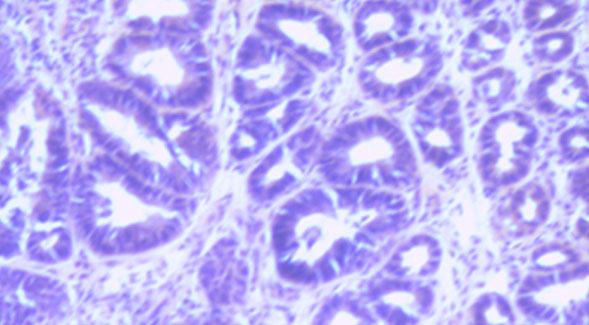

The researchers found a way to identify a biomarker of colorectal cancer in mice. The biomarker, a mutation in the DNA of cancer cells called EMAST (Elevated Microsatellite Alterations at Selected Tetranucleotide repeats), usually is indicative of aggressive forms of colorectal cancer when found in humans. The relatively unknown mutation also is present in some forms of breast, pancreatic, bladder and lung cancers.

Before this research, there was no known method of studying EMAST in animal models, which are critical for conducting basic research that later might be applied to humans.

The discovery creates a blueprint for researchers to study EMAST in animal models and possibly illuminate how the mutation intersects with cancer prognoses.

“How does it occur? How does it progress? How can we treat it?” asked Nitya Bhaskaran, a former graduate student at SDSU. “This is a pioneering study in the field. This research creates a model that can be used to study EMAST while colorectal cancer is in progress, and possibly help discover therapeutic targets for people with the disease.”

Bhaskaran now works at Scripps Research in San Diego as a teaching lab manager. She graduated with a master’s degree in microbiology two years ago, conducting her research alongside SDSU biology professor Kathleen McGuire.

Still in the midst of her research when she graduated, Bhaskaran continued to work in McGuire’s lab long after she received her degree. This fall, Scientific Reports published a paper on their research titled A new method for discovering EMAST sequences in animal models of cancer.

Persistence and teamwork pay off

EMAST occurs when specific, repetitive sequences within DNA are deleted or inserted, causing the genome to be out of order. Earlier studies have found that EMAST is correlated with forms of colorectal cancer that progress faster, are less susceptible to treatment, and are more likely to be fatal.

Yet scientists have not been able to identify all the underlying mechanisms of EMAST, in large part because researchers have not been able to study the mutation in animals.

Bhaskaran used a combination of lab and computer-based techniques to find DNA sequences in mice with colorectal cancer that were similar to the DNA sequences in humans with EMAST mutations in their cancer cells. The work took years and, before there was success, there were plenty of failures.

“I poured my heart and soul into that paper,” Bhaskaran said. “I was a master’s student for three years, and for two years I had no results. This paper was an excellent opportunity for me to communicate the success of my research after navigating many dead ends.”

Originally she and other scientists thought it would be simple to find DNA sequences indicative of EMAST in both humans and mice. Yet the mutation turned out to be very difficult to find in animals. The mouse genome is very repetitive, and isolating the repeat sequences that denote EMAST posed a challenge.

“There were thousands of possibilities, so it wasn’t so easy to know which ones we should look at,” explained McGuire.

Eventually, SDSU biology professor Scott Kelley helped her develop a method of finding and narrowing down possible sequences using bioinformatics. Kelley’s expertise led the team to finally discover point mutations in DNA indicative of EMAST in mice. More work was required to verify their results and publish a paper explaining how other scientists might do the same thing.

The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute. SDSU worked with the University of Michigan on the five-year grant, and received $570,000 to fund research work on this and other cancer-related projects.

Jennifer Luu, who graduated this year with a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry, worked in the lab with Bhaskaran while a student, helping test the genomes of mice for EMAST. She is listed a co-author on the Scientific Reports paper.

She says her time in the lab at SDSU ignited her interest in applied science and helped her get a job at Hologic, a San Diego biotech company.

“Going into the project I had no clue we would find something so big,” she said. “It made me more passionate about research because I got to see all my hard work build into a big discovery.”