New Tribal Liaison Fills Long-standing, High Priority Need

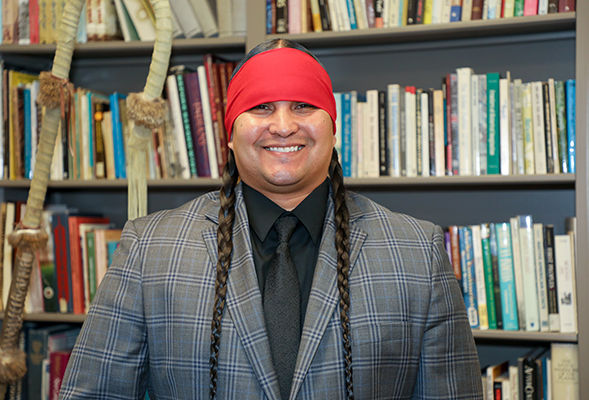

Jacob Alvarado is turning his own passion for education into an opportunity to serve as a welcoming presence for students from indigenous backgrounds.

“I want to create a home here for our indigenous students.”

Some college students can’t wait to get out into the real world. Jacob Alvarado Waipuk couldn’t wait to get back.

Alvarado said he first thought of returning to San Diego State University while he was still earning his BA degree in the Department of American Indian Studies. “I’m coming back here,” he remembers thinking to himself, determined to make a difference for his fellow students from native populations.

Alvarado graduated in 2014 and made good on his dream last week, when the San Pasqual Reservation resident and Kumeyaay Nation member started work as SDSU’s first tribal liaison.

Creating a community-facing liaison emerged as a priority in talks with the Native American community, native leaders and tribal elders, said J. Luke Wood, chief diversity officer at SDSU. “This is in response to what were identified as critical needs from our native community for us to better serve them,” Wood said.

As tribal liaison, Alvarado expects to help recruit and welcome students from indigenous populations and work with the tribal populations of the region, whose two biggest ethnologies are Kumeyaay and Luiseño. Alvarado also will advise the campus on efforts to promote land acknowledgment of the Kumeyaay, which was unanimously approved by the University Senate in September 2019.

Achieving another goal set during his student life, Alvarado also is teaching at SDSU: Issues in American Indian Education (American Indian Studies 480), as a tenure-track assistant professor in the department.

Raelynn Bichitty, a Diné/Chiricahua Apache native currently in her fifth year at SDSU, said the new position means a lot to students like her.

“Seeing an educated, passionate person speaking their native language, practicing their traditions, and helping other succeed academically and personally is the very push that our people need,” she said. “Especially considering that many have lived without such a role model and advocate.”

Kumeyaay tradition

Alvarado is a Kumeyaay traditional singer and dancer; he sang at last fall’s annual convocation and has tattoos on his wrists representing Kumeyaay traditions and culture. Waipuk is his clan name. Alvarado’s daughters, Amu, 4 and Hantuk, 2, are named for elements of Kumeyaay culture.

“Education is going to help our people in a good way,” Alvarado said. “I can help guide you. I struggled to get to where I’m at…but I did it. And if I did it, everybody can do it.”

American Indian Studies chair David Kamper—who personally welcomed Alvarado to SDSU on his very first day as a student—said Alvarado’s hiring fills a long-standing need.

“Some 10 years ago, when I became chair, I tried to meet as many tribal leaders and folks from the community as possible, and the thing I heard over and over again was that the Kumeyaay and Luiseño folks alike wanted their kids to be able to go to San Diego State,” Kamper said. “It’s been one of my goals to make San Diego State a more welcoming place, and a place that serves them.”

“Jacob is a perfect fit for that with his experience working with youth.”

Wood said Alvarado also will work with faculty on an initiative to integrate indigenous perspectives and philosophies into their curricula.

Culture shock

Alvarado noted his firsthand experience with coming to campus straight off a reservation. “When we leave, it’s a bit of a culture shock,” he said. A concerted effort to become more welcoming, he said, gives indigenous students an immediate sense of belonging that can make all the difference over their college experience.

Alvarado made the most of his own SDSU experience by joining the Native American Student Alliance and serving as its president for two years.

He also took a study abroad opportunity at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver under a First Nations Studies Exchange Program, which proved highly influential.

The multiple symbols of support for indigenous populations he saw there, such as totem poles and an on-campus traditional longhouse dwelling, made an indelible impression and conveyed a sense of belonging. Wood noted “there are very few things that are emblematic” of Kumeyaay land at SDSU, although a Native and Indigenous Healing Garden and a Native Student Resource Center both are in the works.

“That’s what I want to do here at San Diego State,” Alvarado said. “I want to create a home here for our indigenous students...and (they) feel comfortable and feel good. We need to talk, we need to express ourselves.”

Raini Tesam-Reading, a Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians native who was a student representative on the hiring committee for the position, said tribes depend on their young members to complete higher education “and then bring that knowledge back to the community.”

“We want to see our own young community members become lawyers, and doctors, and educators themselves,” said Tesam-Reading, who graduated in December with a BA in history. “That’s why the tribal liaison position is such a huge step forward for us.”

Alvarado, who’s in the final stages of completing a joint doctorate at the University of California, San Diego and California State University San Marcos, agrees.

“The main reason I got educated was to give back to my people,” he said. “There’s jobs on the reservation but there’s other jobs where you can help your people as a whole. That’s what I see this opportunity as.”