Almost All Kids Have Tobacco On Their Hands, Even in Non-Smoking Homes

Researchers from SDSU and University of Cincinnati identify disparities in nicotine levels that can lead to respiratory and infectious illnesses.

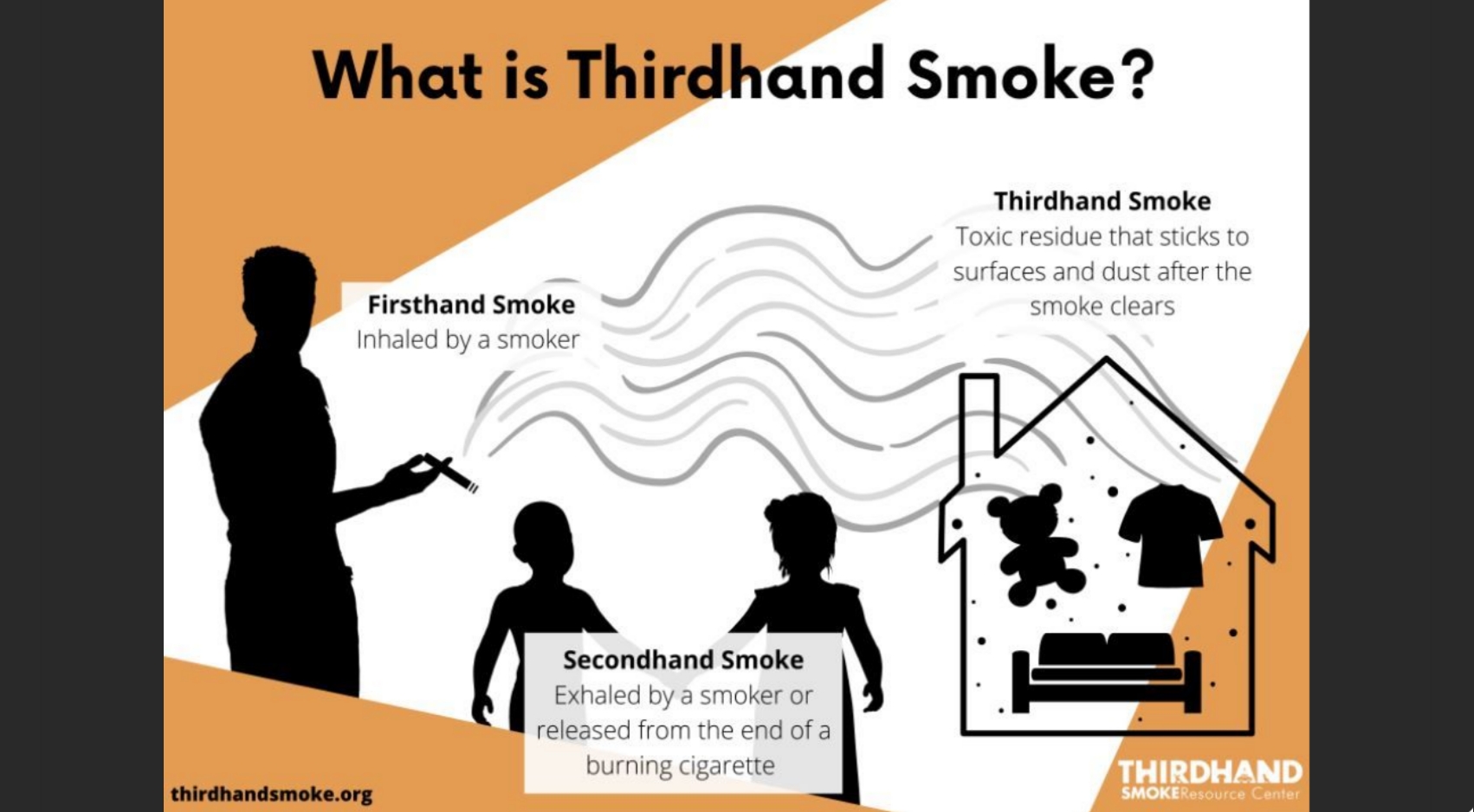

Young children touch everything — carpets, tabletops, toys, clothes, etc. — and then touch their mouths and faces. This makes them especially vulnerable to thirdhand smoke, the toxic chemical residue from tobacco smoke that lingers on surfaces for years after someone smokes or vapes.

Educating parents and other family members about reducing children’s exposure to thirdhand smoke through banning smoking in homes and cars is necessary, but a new study, published in JAMA Network Open, suggests these individual protective measures are not enough.

A team of researchers from San Diego State University and the University of Cincinnati used a novel method of swabbing the hands of children 11 years of age and younger to measure the levels of nicotine present, an indicator of thirdhand smoke exposure.

More than 97% of the 504 children in the study had some level of nicotine present on their hands. More surprisingly, more than 95% of children with no tobacco-using family members and home smoke bans still had nicotine on their hands.

“This study filled an important gap. We have done a lot of research about thirdhand smoke in private homes, cars, hotels, and casinos, but we haven’t had access to clinical populations,” said Georg Matt, a psychology professor at SDSU and director of the Thirdhand Smoke Resource Center.

Importantly, efforts to protect children from tobacco exposure were found to be highly effective in these vulnerable populations. Parental protections like banning smoking inside homes and cars dramatically reduced the amount of nicotine detected on these children’s hands.

Melinda Mahabee-Gittens, a pediatric emergency physician and clinical researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, who led data collection for the project, said, “One result of this research should be to include thirdhand smoke as part of parental smoking cessation education programs.”

The amount of nicotine on children’s hands also varied by income and race.

Children from lower-income families had significantly more nicotine on their hands than children from higher-income families. Children of Black parents had higher amounts of nicotine on their hands than children of white or multiracial parents.

“Low-income children and children of Black parents have the most of this involuntary exposure; this is a wake-up call to protect vulnerable children and is an overlooked part of housing disparities,” said Penelope Quintana, a public health professor at SDSU and co-author of the study.

“With COVID, everybody is spending more time indoors and more time at home. If you live in an environment where people smoke or used to smoke, you’re going to be more exposed to thirdhand smoke than you were before,” Matt added. “This study further highlights the importance of the quality of indoor environments.”

The researchers plan to continue analyzing other markers of thirdhand smoke exposure and investigate health outcomes. They hope their research will further support stricter smoking bans, remediation practices, and policies requiring real estate agents and landlords to disclose thirdhand smoke levels in homes.

The Thirdhand Smoke Resource Center is funded by revenues from a cigarette tax increase approved by California voters in 2016. Additional funding was provided by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Institute on Drug Abuse.