The Sequoia of Spiders: A New Species of Ancient Arachnid

SDSU biologists identified a new lampshade spider species in the southern Sierra Nevada.

In the cool shade of tall conifers, nestled on the faces of granite boulders strewn throughout the river and creek beds of the southern Sierran foothills, orange, beige and black spiders with bodies smaller than pencil erasers lay in wait in their lampshade-shaped webs.

One of these spider species, whose earliest ancestors lived in the time of the dinosaurs, was newly identified by San Diego State University biology professor Marshal Hedin and his students.

“Describing a new species of Hypochilus is really cool. It is a great accomplishment, and I’m very proud of that,” Hedin said.

A new species in this genus has not been identified since 1994, with the first identified in 1888.

“Hypochilus are kind of like the Bigfoot of the spider world. They’re really special and from an older time,” Hedin said.

Like the towering sequoias, Hypochilus spiders are what is called paleoendemic, meaning they were previously widespread in a region but are now more geographically restricted.

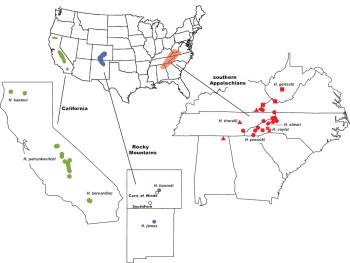

The new spider species, Hypochilus xomote, is named for the Yowlumni word for south because the spiders are the southernmost known Hypochilus populations found in the California Sierra Nevada. Hedin’s group found these spiders on the western side of the Sequoia National Forest, about 80 miles northeast of Bakersfield, on lands historically occupied by the Tule River Yokuts people.

Other related species can be found in the Rocky Mountains and the Appalachians.

To make the case that H. xomote are distinct from other spiders, SDSU biology alumnus and U.S. Navy veteran Andrew Debray (‘21) used the scanning electron microscope on campus to identify differences in adult male pedipalps, appendages located near the spider mouthparts.

Debray, who as a child examined dirty water from the backyard under a briefcase microscope for fun, now uses his “terrific know-how” and skills with electron microscopes as a research and development associate at Nano PharmaSolutions, a startup in Sorrento Valley.

Combining Debray’s images with the genetic analyses conducted by graduate student Erik Ciaccio provided enough evidence that H. xomote are diverging from other morphologically identical species due to their fragmented habitats.

Spiders do not travel between drainage basins, so populations that may only be a few canyons apart can be vastly different evolutionarily, with each generation living only one to two years. These small niches can be destroyed by one localized fire that burns all of the tree cover, resulting in rocky habitats that are too hot and dry for the spiders to inhabit.

“Identifying new species is something that people need to pay attention to. You learn about the special biodiversity that’s not found anywhere else,” Hedin said. “The place itself becomes more interesting; you want to conserve the place.”