What is Monkeypox? Q&A with SDSU Professor Richard Shaffer

SDSU professor of public health discusses this years global outbreak of the zoonotic disease.

Until this year, few people in the United States had heard of monkeypox. Previous outbreaks have largely been confined to central and west Africa, though an outbreak linked to exotic pets infected people in six U.S. states in 2003.

Richard Shaffer is a professor of epidemiology at the San Diego State University School of Public Health and director of SDSU’s joint doctoral program in epidemiology with the University of California, San Diego.

NewsCenter’s Susanne Clara Bard asked Shaffer to explain what’s behind the new outbreak that was recently declared a global health emergency by the World Health Organization.

What is monkeypox?

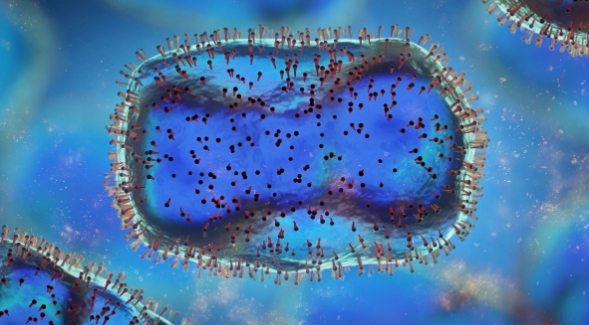

Monkeypox was first identified in populations of captive monkeys in central Africa in 1958. The first case in humans was identified in the same region in the early 1970s. The disease is caused by a virus in the genus Orthopoxvirus. The most well known disease to have been caused by an Orthopoxvirus is smallpox, but the monkeypox virus is a different species (virologic subgroup of a genus) than the smallpox virus. Interestingly, the natural reservoir for the disease is not monkeys, but rather smaller mammals, but both humans and monkeys can get the disease from those smaller mammals, and humans can transmit it to each other. Prior to 2021, the disease was limited to just a few hundred cases a year almost entirely in central and western Africa.

Why is monkeypox in the news lately?

In 2021, cases were seen outside of Africa, but unlike prior years, the cases outside of Africa were not only seen in people who recently traveled to Africa, cases were being transmitted from person-to-person among people who had not traveled to Africa. By August 1, 2022, more than 22,000 cases were observed on six out of seven continents worldwide. The U.S. has the second highest number of cases worldwide with more than 5,000 cases. While the disease is still very rare, this represents a significant increase in cases and novel means of transmission from prior years. There are several theories for this increase, but one is that the previously administered smallpox vaccine provided protection against monkeypox. Smallpox vaccination was stopped in the general population over 30 years ago, and a growing proportion of the population is unvaccinated.

What are the main symptoms of monkeypox?

The symptoms of monkeypox are fever, general malaise (feeling unwell) muscle aches, headache, exhaustion, swollen lymph nodes and the classic “pox” which is a “pimple-like” rash on various parts of the body. Sometimes the rash appears first and other times the other symptoms can appear before the rash. Monkeypox is typically a mild disease, but while there have been no deaths from monkeypox in the U.S., the current disease can have more severe symptoms and there have been a small number of hospitalizations in monkeypox patients. These hospitalizations have been from pain from the rash due to the location of the rash on the body. The rash is typically only moderately painful but if it occurs in the mouth, anus or genitals, the pain can be severe and require hospitalization.

What is the risk to the general population?

As of August 1, 2022, the risk of monkeypox to the general population is very low. There are about 5,000 cases in the U.S., 800 in California, and 27 in San Diego County. The risk of death from monkeypox is nearly zero. In the U.S., the disease is almost entirely in adult men, but the distribution of disease can certainly shift if people aren’t aware of the disease and take precautions. Certain groups need to be especially vigilant, with the vast majority of cases being in men who have sex with men. At risk is anyone whose intimate partner has monkeypox or anyone who has had recent physical contact with a person with monkeypox. Persons who suspect they have symptoms or that they have had a significant exposure, should contact their health provider who should contact the health department if monkeypox is confirmed. The suspected case should also refrain from physical or intimate contact with others until their condition has been determined. There are many resources that can help keep updated on the status of monkeypox, with the best resource being the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.

How is monkeypox treated?

There are several treatment options for monkeypox. The first is a drug developed to treat smallpox (Tecovirimat), which has shown to be successful for monkeypox. There is also success with a treatment normally used for rare patients who had a reaction to the smallpox vaccine (VIGIV) if the first treatment is not indicated. Treatment with this drug is currently reserved for hospitalized patients or patients who are immunocompromised or children because the disease in other patients is typically minor.

How is monkeypox transmitted from one person to another?

Monkeypox is transmitted from person-to-person, or through contact with an infected animal. The disease is not transmitted by the respiratory aerosol route. It is transmitted by contact (touching) with an infected patient with the rash. The monkeypox rash is contagious until the scab breaks off and there is normal skin beneath. It can also be transmitted by coming in contact with bed sheets or clothing from an infected person with the rash. It can also be transmitted by prolonged face-to-face contact (kissing) and intimate physical contact. While the disease can be transmitted during sex, it is mainly a result of physical (skin-to-skin) contact and is not limited to the genitals, anus, or mouth. The disease can also be passed from an infected pregnant woman to her unborn baby. The disease can be prevented by avoiding physical contact with an ill person, by washing clothes and bed linens from ill persons, and disinfecting surfaces touched by an ill person.

Is there a vaccine? If so, who should consider getting vaccinated?

Monkeypox is a vaccine-preventable disease and there are currently two vaccines that prevent the disease. The first option is the JYNNEOS vaccine which is two shots four weeks apart, with a booster every two years. It is currently in limited supply so as a “primary prevention” (vaccine for persons who have not been in contact with an infected person) the vaccine is currently only available for health care workers working with infected patients or laboratory workers. However, this vaccine is also being used as a post-exposure prophylactic (PEP) for individuals with a documented contact with an infected person. The second vaccine is ACAM2000, which also works well but is not indicated for people with health conditions such as a weakened immune system, skin conditions, or pregnancy.