Fire Science in the Age of Humans

SDSU researchers join call for a more collaborative and inclusive approach to fire science in an increasingly fire-prone world.

Devastating wildfires have become a staple of life in California and across the West Coast. The 2018 Camp Fire and the 2017 Thomas Fire are just a few notable examples, and according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, 2020 set a record for most acres burned.

“Here in Southern California and across the Southwest, ecosystems evolved with fire,” said San Diego State University ecologist Megan Jennings. “They did not evolve with this amount of fire, nor under the conditions that we're seeing now.”

While a combination of factors including drought, urbanization and historical fire management practices make this area of the world particularly vulnerable, fire danger is increasing across the globe, with climate consequences.

“In the Amazon, we have really ramped up the amount of fire over the last couple of decades,” said SDSU geographer Fernando De Sales. “By burning the trees, we release a lot of carbon dioxide, so even though it's a regional phenomenon, that CO2 goes to the atmosphere that we all share and contributes to global warming.”

Public health and economic stability are also imperiled. In 2021, Jennings and De Sales met with researchers at the National Science Foundation sponsored Wildfire and the Biosphere Innovation Lab to envision new approaches to fire science that address the worldwide wildfire crisis. They published their recommendations in the journal PNAS Nexus.

Cross-Disciplinary Solutions

One problem the authors identified is fire researchers don’t always consider the bigger picture.

“A lot of times in the sciences, we tend to approach things in silos within our discipline,” said Jennings. “Where we are now with fire, we need to be working together.”

Instead, researchers who study the soil chemistry, ecology and physical dynamics of fire could gain important insights by communicating with public health experts, economists and social scientists who consider fire’s impact on people’s lives.

Anthropologists, for example, study how fire has been part of human existence from the very beginning and how that relationship has changed over time, said De Sales.

“It's going to require these connections to really make any sort of notable change,” said Jennings.

Legacy of Fire Suppression

Jennings believes it's a mistake to think that all fire is bad.

"When it's good fire, it can provide renewal, a flush of nutrients. It hits a reset button and allows for new things to take root and grow,” she said.

However, deadly and destructive wildfires during the early part of the 20th century prompted the U.S. Forest Service and other land managers to adopt a policy of full suppression.

“And they've been very effective at that for over a hundred years, but there was an ecological consequence.”

In forested areas, fire suppression leads to dense growth and an accumulation of fuel that feeds wildfires, said Jennings. There have been social consequences as well: as the atmosphere has warmed, it has become harder to suppress mega fires.

“We have 25 million people living in Southern California now. We were so good at fire suppression, people felt comfortable putting their houses here,” said Jennings. But that’s not sustainable without continued fire suppression. “So, we're sort of stuck in this place where suppression is still necessary.”

Fire suppression also impacted Indigenous communities in the region, which have always included fire in their stewardship of the land.

“They tend to be small fires, burning to promote growth of key plant speciesm,” she said. But fire suppression policies also suppressed fire within those tribal communities. What's more, Indigenous people are often not included in the stewardship of the vast majority of their traditional ancestral lands outside of reservation boundaries.”

In their paper, the authors identified the importance of drawing upon insights into fire management and resilience from a variety of perspectives, including Indigenous communities.

Another recommendation is to turn to fire as a powerful force throughout human history that can shed light on a variety of sciences, from human evolution to ecology. “A way to create a whole list of new questions that maybe we haven't asked yet,” said De Sales.

The authors also believe in tapping into the constant flow of information that accumulates outside of academia.

“Data collected from social media, like Twitter or Facebook, to try to see where the next fire will start,” said De Sales. “Because people tend to cluster together and they tweet about it.”

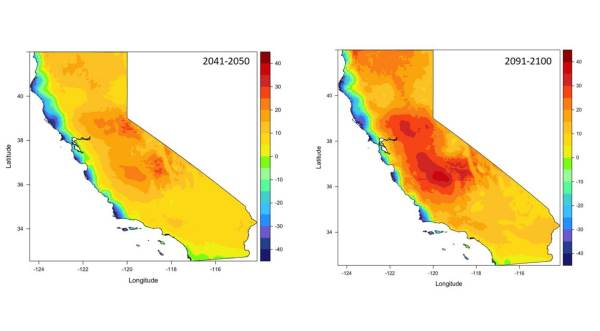

Finally, the authors recommend developing models of fire that draw upon the social sciences as well as the natural sciences. For example, accounting for the human element in igniting some fires.

“If you don't have that spark, it doesn't matter if it's dry and hot, you won't have a fire. And that's where the human component perhaps plays a big role,” said De Sales. “If we could incorporate that in the models themselves, that would be a huge step in what kind of predictions we can come up with.”

California wildfires have been relatively modest this year in comparison to the past few years — so far, anyway. According to Jennings, some of this is due to luck, for example, a drenching from tropical storm Kay in early September 2022 likely blunted the destructive potential of the Fairview Fire in Riverside County. But the situation could easily change.

“Our fire season is not over. Right now, at least in Southern California, we're entering the danger zone of Santa Ana season,” said Jennings.

These powerful winds push hot air from the mountains toward the coast — drying out combustible vegetation. Lately, they’ve fanned the flames of wildfires well into December, rendering the term “fire season” obsolete.

“The Santa Ana season is the fall and winter — with October and November being the prime months for large fires associated with these winds — but we now see large fires throughout the year,” said De Sales.