Caring for Late Father Inspires SDSU Alumnus to Improve Indigenous Cancer Health Care

Continued connections to SDSU programs and Native community keep him going.

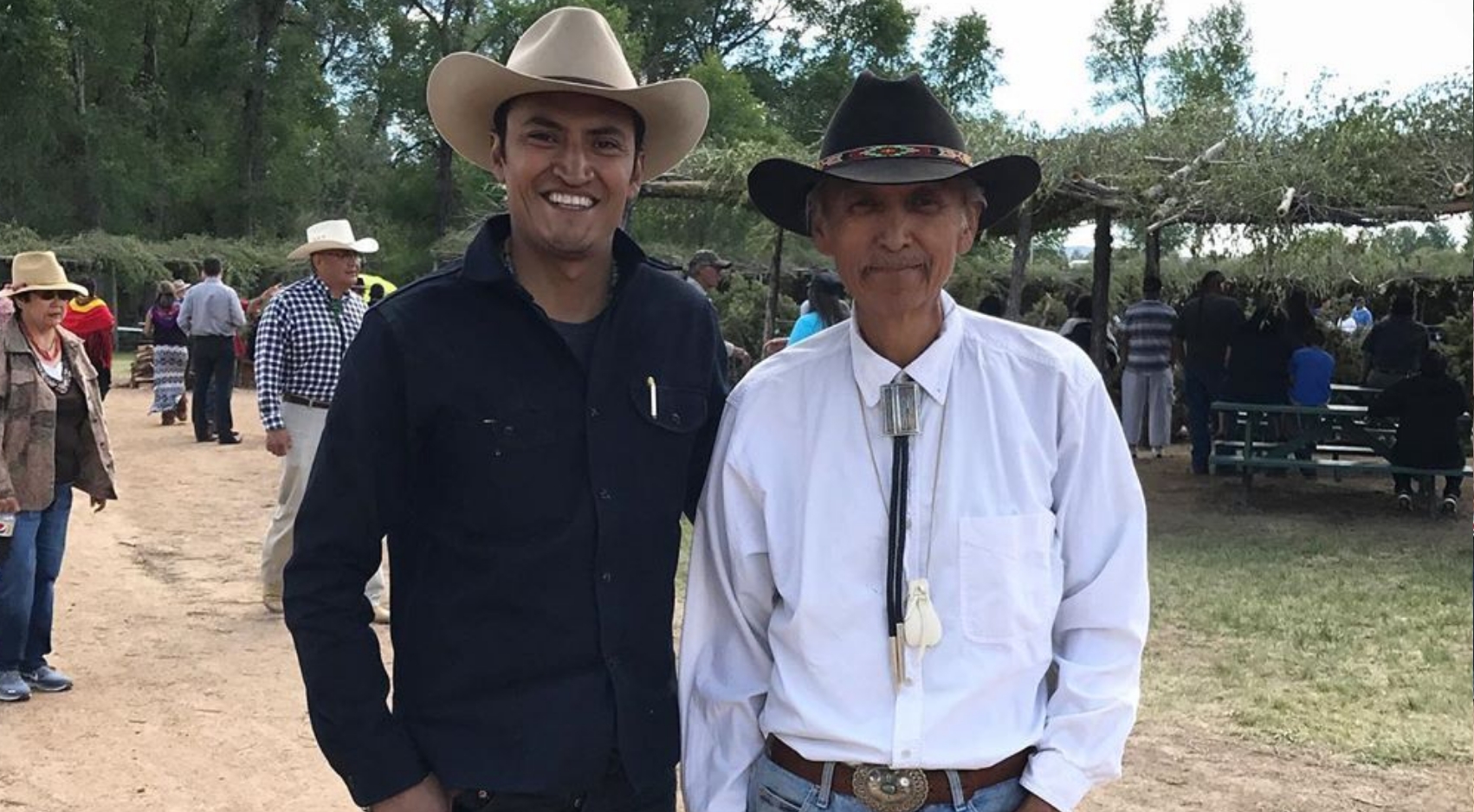

Moving from New Mexico’s Navajo Nation to San Diego prepared Marc Emerson (‘08, ‘12) for a long journey to his current career as an epidemiologist investigating how patients and their caregivers cope with a cancer diagnosis.

Influential mentors at San Diego State University and their programs for underrepresented scholars changed his trajectory from selling electronics full-time to passionately preventing Indigenous health disparities, a calling more personal than he initially anticipated.

If not for the guidance he received at SDSU, Emerson said, “I probably never would have landed where I am now.”

The Path to Epidemiology

In his first years at SDSU, Emerson found community living on the Sycuan reservation of the Kumeyaay Tribe and in Zura residence hall while working full-time at Circuit City. Then, financial support from what are now the Maximizing Access to Research Careers (MARC) and Initiative for Maximizing Student Development (IMSD) programs allowed him to quit his job to pursue a meaningful summer research opportunity.

Through connections provided by his SDSU mentors, Emerson interned with the Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health. For a summer, he transcribed interviews about parental and father involvement in White Mountain Apache and Navajo communities, echoing his own experiences living with his father for the first time as a teen.

Back in San Diego, he worked with SDSU psychology professor Vanessa Malcarne and African American cancer survivors at Moores Cancer Center to better understand their lived experiences before, during and after a cancer diagnosis and treatment.

These experiences made him think he wanted to become a doctor or psychiatrist working with Indigenous youth. He took numerous pre-med courses in addition to his psychology major coursework. But when only one medical school program accepted him, Emerson went back to the drawing board.

Talking with mentors from his previous SDSU programs, he decided to earn his master’s in public health (MPH) at SDSU with the goal of reapplying to medical school. But he never reapplied. Instead, he fell in love with epidemiology as a field.

“It was easier to connect the dots from the coursework to what I wanted to do,” Emerson said. “The MPH directly applied to the methods and the work that I think is important.”

With the dream of medical school long forgotten, he entered a doctoral program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with a focus on health in Indigenous communities.

Braiding in Native Identity

In the third year of his Ph.D. program, Emerson had to put his new life on pause. His father was diagnosed with late-stage stomach cancer, so he moved back to New Mexico to be his primary caregiver.

Driving three hours each way to Albuquerque for appointments and surgeries made Emerson’s research on healthcare access and interventions among Native populations more relevant than ever before.

“Losing my dad was really hard,” Emerson said. “That was a really impactful experience that has reinforced my drive and motivation to do the work that I do in cancer research and cancer health inequities.”

After earning his doctorate, Emerson secured a position as an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which he said was bittersweet because his dad never got to see this success.

But he’s continuing his father’s legacy as a Native leader building a comprehensive cancer center in collaboration with the Lumbee and Eastern band of Cherokee communities in North Carolina.

He also readily volunteers his time for SDSU students in the MARC and IMSD programs, led by his mentors Thelma Chavez and Cathie Atkins.

“I can be a Brown face for these students interested in STEM,” Emerson said. “It’s important to be available and present and a type of representation for those who were in the position I was in.”

“Even as a young scholar, Marc demonstrated he was a remarkably ethical individual whose feelings and thoughts ran very deep,” said Atkins. “He was genuinely concerned about how he could have an impact in this world. His commitment to his community was and is profound.”