Don’t lose your head over it!

SDSU undergraduate Yesenia Rodriguez Reyes tackles a biological mystery when nematodes turn up without their heads — and bacteria become the prime suspect.

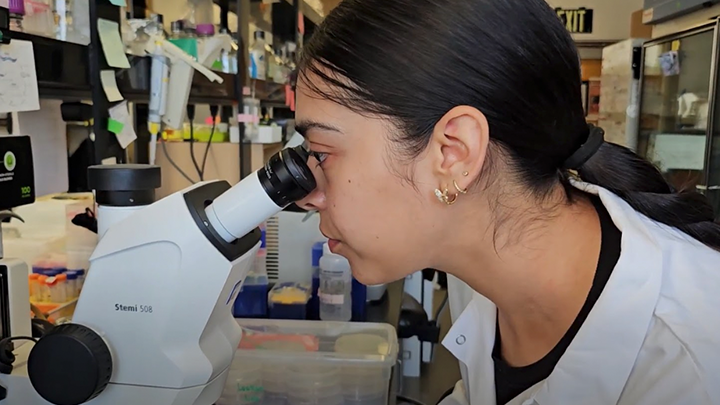

It seemed like a normal fall day in 2023 as participants in biologist Robert Luallen’s Host-Bacteria Interactions Workshop collected rotten kumquats from a tree on the San Diego State University campus. Back in the lab, they looked for tiny worms called nematodes within the decomposing fruit. But when the students examined these nematodes under a microscope, there was a problem.

Something had cut off their heads.

“We could see the whole bodies of the nematodes, but the head was just like detached from the body,” said chemistry major Yesenia Rodriguez Reyes, a workshop participant. She says no one in the Luallen lab had ever seen this before.

Using a lab technique called fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) the students observed the telltale green glow of infectious bacteria inside the worms. Could the microorganisms be suspects in the beheading?

Rodriguez Reyes was on the case. After the workshop — which was designed for first-generation college students — she joined Luallen’s lab, spending the spring and summer of 2024 investigating the mystery of the headless nematodes as part of the SDSU Undergraduate Research Program (SURP).

RELATED: My, How You've Grown: New Species of Bacteria is a Shapeshifter Extraordinaire

SURP matches undergraduates with faculty mentors, providing stipends to make research, scholarly and creative opportunities accessible to more students. At the end of the program, they present their findings to their peers and to faculty. The program prepares the participants for graduate school and future careers.

“Doing hands-on research drives home the theory they learn in their classes,” said Luallen, an assistant professor of biology. “Not only do they get to experience research, but they're also providing us a benefit by discovering new things.”

Rodriguez’s goals for her SURP project were to identify the enigmatic bacteria, understand their life cycle, and discover whether they were the culprit in the decapitation enigma. And if so, how did they pull off this nefarious act?

To solve the mystery, Rodriguez Reyes would need to learn many forensic tools. Under the guidance of Anupama Singh, a postdoctoral research fellow, and Truc Nguyen (Microbiology, ‘23), a research assistant in the Luallen Lab, Rodriguez Reyes became proficient at several advanced molecular biology techniques and how to grow nematodes in the lab. She ran genetic tests using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and metagenomics to identify the species of the bacteria. She used fluorescent microscopy to discover what part of the nematode’s body was being infected by the bacteria. And she used in vitro bacterial techniques to understand the lifecycle of the bacteria and how it infects the worm. She also learned how to test scientific hypotheses and run statistical tests on her data.

“Mentoring Yesenia is like shining light in a direction, she takes the hint and leads the way,” said Singh. “I’ve seen her quickly learn lab techniques and skills, honing her research aptitude and becoming more confident. And the adventure continues for her.”

Rodriguez Reyes’s detective work paid off. Her research revealed that not just one, but two bacterial species were living inside the nematodes. But only one of them, Leucobacter celer, appeared to be the perpetrator of the decapitations.

The species is known to produce a sticky biofilm that traps the worms by their tails, forming a “worm star” that radiates outward from a central point — making them easy prey for the bacteria to feast upon.

“When the worms try to crawl away, some get ripped in half and some get decapitated,” said Luallen.

Rodriguez Reyes presented her findings at the annual SDSU Student Symposium (S3) and at a SURP celebration in August. She also plans to write a paper on the results of her investigation for publication in a scientific journal.

First-generation scientists

Rodriguez Reyes was born in San Diego and grew up in Tijuana. She returned to attend Chula Vista High School in the 9th grade. During her sophomore year, an inspiring chemistry teacher shared her own experiences with biochemistry research.

“I was completely fascinated by it. And I thought that it was something that I would want to do,” she said. She was soon earning community service credit for mentoring her classmates in STEM.

Rodriguez Reyes was the first person in her family to go to college. When she arrived at SDSU in fall 2023 as a transfer student from Southwestern College, she had big dreams.

“Before transferring here, I didn't have any lab research experience, which I thought was going to affect me,” she said. But when she saw none was required for Luallen’s Host-Bacteria Interactions Workshop, she reached out to Luallen and applied.

Luallen designed his Host-Bacteria Interactions Workshop for first-generation college students like Rodriguez Reyes, drawing on his own experience.

“The reason I planned this workshop is because as a first-generation college student myself, not knowing that there were research opportunities for me — even though I knew I was really into genetics — really kind of hindered me,” he said. “And so the workshop itself starts out as a primer for whether or not the students are interested in doing research.”

Rodriguez Reyes is definitely hooked. Fingering the perpetrators of the nematode beheadings opened up a whole new can of worms. She also discovered that only female nematodes get stuck in worm stars, while males escape unscathed. She’d love to know if there is something special about their tails that wards off the bacteria.

“Right now we are considering following up on this by studying why male worms don’t get stuck in worm stars but only female worms do,” said Luallen.

After SDSU, Rodriguez Reyes hopes to get a master’s degree in chemistry and go on to conduct research for the pharmaceutical industry.