New book uncovers skateboarding and surfing's ties to socio-political movements

SDSU professors and others from around the world explore new perspectives on surf/skate subcultures and the relationship to issues of climate change, economic inequality, racism, and authoritarianism.

During the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in 2020, after the murder of George Floyd, skateboarders flocked to downtown San Diego to show their support at two “Rolling for Rights” events. Thousands of skateboarders participated in street takeovers in peaceful protest and garnered attention from the news media, who were surprised that the skaters were using their voices in a positive way. Surfers also gathered at Moonlight Beach in Encinitas for a paddle out and event to show their BLM support.

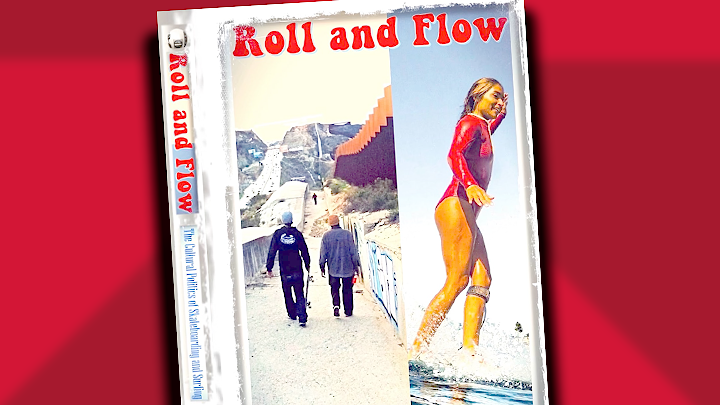

“Roll and Flow: The Cultural Politics of Skateboarding and Surfing,” a new book co-edited by Michael James Roberts, professor of sociology, David P. Cline, professor of history, and Kristin Lawler, professor of sociology at the University of Mount Saint Vincent, New York City, points to the fact that skateboarders and surfers have had a long history of confronting police authority — and modern socio-political problems.

“When you combine that history with how the skateboarding community has become much more diverse in the last couple of decades, it makes sense that skateboarders were so active in Black Lives Matter,” Roberts said.

After Roberts noticed these connections, he began to think deeply about the history of skateboarders and surfers surrounding other progressive social movements. He wanted to explore the connections to feminist, LGBTQIA+, and labor movements in addition to political movements.

He found that academic articles mostly focused on how skateboarding and surfing relates to a consumer society or as pop culture phenomena. “I wanted to introduce another perspective that would complement this older academic perspective,” Roberts said. “I’m interested in the progressive political histories of these two lifestyle sports.”

The new book with 15 chapters features the work of 21 scholars from the U.S., Italy, England, UK, Germany and Sweden, and focuses on topics related to progressive socio-political movements.

“The variety of pieces and the insights from vastly differing fields and perspectives is close to breathtaking,” Cline said. “Surfers and skateboarders as stakeholders and caretakers of a fragile environment is one throughline that permeates the collection.”

Chapter Highlights

Lawler and Roberts co-wrote a chapter about their research on the cultural overlaps between surfing subculture and the labor movement. They found that a group of surfers in the 1930s at San Onofre State Beach, would sing old labor songs like, “Hallelujah, I’m a Bum” or “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” originally recorded in 1928 by Harry McClintock, a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

“This fact, relatively unknown in both surf studies and in labor history, makes plain the class politics of surf culture at its early California roots as well as the concrete links between two of America's most seminal countercultural forms,” Lawler said. “The similarities between IWW hoboes and early California surfers are striking and shed light on important questions of the politics of work and of culture that, we believe, are as relevant now as they were a hundred years ago.”

In Andrea Buchetti’s chapter “A Matter of Detalles: On Producing and Consuming the Skateboard Industry on the U.S.-Mexico Border,” he looks at globalization of the industry. Robert’s said this chapter offers fascinating original research by an Italian scholar and anthropologist who lived in Tijuana for two years. Buchetti found that skaters who worked in the Maquiladora factories making skateboard decks find unique ways to connect with skate culture on the other side of the border. While they were not able to physically participate in the U.S. skateboard culture, they still found a way to connect with skaters across the world through special marks they put on the boards. In short, Buchetti races what he calls the “social biographies” of skateboards.

In “Polluted Leisure in Grey Space: The Case of Salubrious Superfund Skateparks,” Brian Glenney looks at the politics behind the expansion of public skateparks and reveals that some are built atop what the EPA considers toxic brownfield sites.

Elliot Pill offers a critique on the industry of professional surfing. He enters the debate on whether or not surfing should be considered a sport. He asks, what are the so-called negative implications of the giant growth of surfing competitions and the companies that control them.

Keith Plosek looks at the media and ideology in terms of how figures of authority attempt to discipline surfers. He talks about the shark not just as a physical animal, but the shark becomes a symbol of authority. “If you don’t conform to society, then you’re at risk of being ‘eaten by the shark,’” Roberts said.

In the final chapter, former professional surfer Cori Schumacher from Carlsbad writes about surf culture as a way to rethink political problems facing the public today around authoritarianism and the threat to democracy. “She looks at how surfer subculture provides a unique perspective on politics and her concern is to think about ways to resist the rise of authoritarian politics around the world,” Roberts said. “How the perspective of a surfer provides a critical way to think about and promote diversity and come to terms with a rise in authoritarian regimes.”

Roberts notes that people tend to try to separate politics from sports and that sports are often thought of as an escape from politics. In the book, however, the essays reveal that many skateboarders and surfers are deeply engaged with politics.

Roberts' hope is that this book is the beginning of a broader investigation into the relationships of surfing and skateboarding subcultures to progressive politics.

The anthology is published by SDSU Press and available through Amazon.