At the ‘Top of the World’

SDSU researchers measure climate change in areas of Alaskan tundra where few modern humans have set foot

This story was originally published in SDSU Magazine.

For decades, San Diego State University researchers have traveled to Utqiaġvik, Alaska—occasionally packing their own portable toilet along with muck boots and bear spray—to document the dynamics of climate change in the frigid tundra.

SDSU students, under the guidance of biology professor Donatella Zona and local Indigenous partners, spend months monitoring seasonal fluctuations in greenhouse gasses, frozen soil depth and plant growth. Their work has shown that the Arctic releases large amounts of methane, partially explaining why the region is warming faster than any other place on Earth. Accessing new locations, like the tundra beyond traditional Arctic hunting routes, can provide insights into lingering questions about what can be done to protect ecosystems and people.

Open the image full screen.

Open the image full screen.

Above the Arctic Circle, Utqiaġvik (named for the Iñupiaq word for where snowy owls are hunted) is home to fewer than 5,000 people. Point Barrow is 9 sandy miles north of town and can be accessed only by foot, 4x4s or ATVs. Here, subsistence hunters pile bowhead whale carcasses to lure polar bears away from the populated areas. Whale bones often adorn the beaches and the city streets, and locals enjoy chewy bits of whale blubber and dark meat as frozen delicacies.

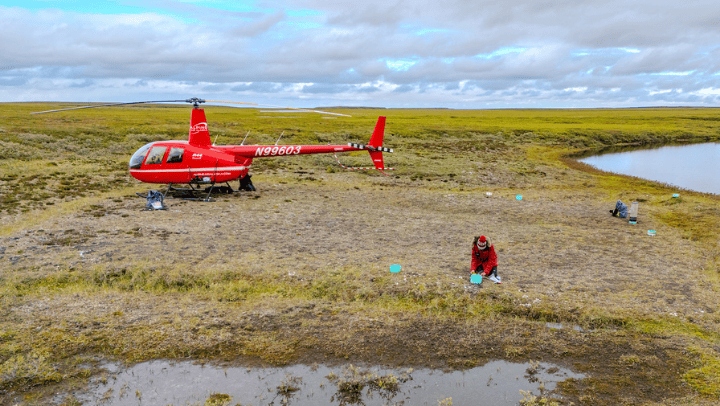

Researchers use satellite imagery and other sensor data to identify the most promising remote sites to gather information about prominent factors in global warming. Their selections require: 1) elevated mounds with both plant growth and unvegetated soil and 2) locations with streams from previously drained lakes to track the full spectrum of greenhouse gas emissions.

These areas are reachable only by helicopter—and only when the weather cooperates.

Open the image full screen.

Open the image full screen.

From the helicopter, Francia Tenorio, an SDSU ecology Ph.D. student, scans the horizon for migrating birds, polar bears, brown bears and caribou before the pilot safely lands in the untouched tundra, Tenorio’s lab for the day.

Open the image full screen.

Open the image full screen.

When ecology doctoral student Macall Hock arrived in Utqiaġvik in June, sea ice still dotted the coastline. Since 2021, she has spent her summers living in “the Nest” research dormitories with intermittent internet, trekking out to the tundra almost every day to track seasonal changes in carbon emissions in streams. Enduring initial snowmelt, mosquito-infested heat waves and rainy Augusts, Hock frequently repaired and recalibrated her sensors, deploying them inside of a floating chamber—a metal mixing bowl taped to a pool noodle—on the stream surface.

“Research in the Arctic isn’t glamorous, but studying climate change in Alaska, especially with a focus on local and Indigenous communities, has been so transformative for my work and can inform solutions for ecosystems and people facing the effects of warming everywhere,” said Jacqui Vogel, SDSU geography Ph.D. student.