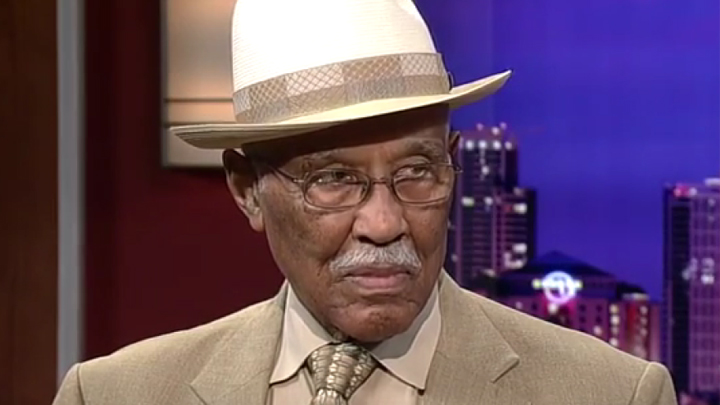

In Memoriam: Leon Williams

The SDSU trolley station is dedicated to the former councilman and transit board member, who was associated with the university for decades.

Updated March 7, 2025

Decades after his own time as a student at San Diego State College, Leon Williams (‘50) pushed a vision for his alma mater that would transform the modern-day campus.

Williams served on the governing board of the region’s public transit agency for its first 29 years, 12 as chairman. As the Metropolitan Transit Development Board (MTDB) considered multiple alternatives for extending the San Diego Trolley east from Mission San Diego, Williams became a forceful voice for a station right on campus. A far less costly option would have placed the San Diego State University station on the northern border of campus alongside Interstate 8, but Williams felt students wouldn’t use such an inconvenient location.

“We put it on the fringe, it’s going to be a fringe thing,” Williams recalled later in an oral history. “We gotta put it in their face so they can’t miss it.”

The campus alternative was much more of an engineering challenge, requiring a 4,000-foot tunnel and the only underground stop in the trolley system. Opened in 2005 and now one of the gems of the trolley system, the station in 2011 was dedicated to the man who insisted it serve the heart of the university.

Williams died March 1 of cardiac arrest. He was 102.

Williams endured the brutal indignities of San Diego’s Jim Crow era to become the first Black member of both the San Diego City Council and the county Board of Supervisors. Once described by prominent social activist Vernon Sukumu as the Jackie Robinson of San Diego, he never lost a campaign. His three decades of community service are the subject of a special collection in the SDSU University Library archives, and a presentation room on the fourth floor of Love Library is named for him.

A soft-spoken but eloquent speaker, Williams was the rare public official who seemed to charm everyone with whom he worked. “If you want to get results, you can’t make enemies of all the people in power,” Williams told writer Lynne Carrier for her biography “Together We Can Do More” (2015, Montezuma Publishing).

In any political disagreement, Williams said his approach was “let’s see what we can do.” For the SDSU trolley station, he argued that the higher expense of an on-campus station would pay off over time.

“They took into consideration my view that this is an investment, you don’t just get (return on) it today, you get it over time, and reduce the automobile traffic,” he said. “If we create transit riders (among students)...that’s what they learn as youngsters. And so that helps us in the future. So we did it.”

Larry Piper, campus transportation planner at the time, recalled an “epic campus tour with Leon and MTS leaders, which marched along the northern edge of the campus mesa to see the elevation of 10 stories or more down to the freeway station alternative.

“Leon’s observation was something like ’That’s no place to put a student station,’” Piper said, “and he was right of course, and had the foresight and perseverance to see that building a tunnel and an underground station was the only viable alternative.”

Piper, now retired, said Williams also had a major role not only in discussions to meet the university’s many demands for the trolley project, but in the negotiations with California State University and with federal funding sources needed to bring it to reality. “This commitment and all it entailed, that was Leon’s legacy,” he said.

The station had more than 2,100 daily boardings in spring 2024 and nearly 2,700 the previous fall, according to MTS figures.

Career path

Leon Lawson Williams and his family moved from their farm in Oklahoma to Bakersfield during the Great Depression, when Leon was 14. In a 2008 interview at SDSU for an oral history, Williams said he longed to attend college at UCLA, but in 1941 moved to San Diego for a job at North Island Naval Air Station. After serving in the military during World War II in a segregated Army unit, he enrolled at San Diego State College on the G.I. Bill.

Williams had credits from a junior college already under his belt and completed a bachelor’s degree in psychology in two and a half years, and recalled that he was one of few Black people on campus. “There were not very many,” he said.

Williams remembered being in the Psychology Club, Toastmasters and other organizations, but said “we were not allowed to participate in the student government, much of the real activities. We were kind of on the fringe of campus life.”

In the broader San Diego community, overt racism was a persistent experience for Williams. Many restaurants refused to serve Black customers, and Williams recalled participating in sit-in protests at restaurants with other San Diego State students. His purchase of a home in San Diego’s Golden Hill community in 1947 defied a whites-only covenant for the area at the time.

His degree led to a job with the county department of social services, and Williams went on from there to work in administration for the Sheriff’s Department. In 1966, he became director of the Neighborhood Youth Corps program, administered by the Urban League.

With support from a multiethnic community group, Williams was appointed to the City Council in 1969 to fill a vacancy in the Fourth District which at the time included the city’s then-shabby Downtown, the broad region known as Southeast San Diego, and San Ysidro. He was subsequently elected to the seat four times. In an era when the top two council candidates in a district election were required to face off in a citywide runoff where white voters constituted a majority; Williams notably amassed 60% or more of the vote.

“City government was not very responsive to African Americans and African Americans didn’t expect the government to do much for them,” Williams said in a 2015 interview with KPBS to publicize the new biography. “It was a very divided and from my point of view unhappy, unwholesome situation.”

Council salaries were a paltry $5,000 at the time and Williams supplemented his income with part-time teaching assignments at San Diego State and, according to his biography, a campus yogurt shop he later sold.

Even as a councilman, Williams experienced systemic racism. He frequently told of the time he was pulled over by a police officer, while driving in a white neighborhood, on the pretext of a broken taillight.

Policy interests

In his oral history, Williams ― who rode streetcars both in Bakersfield and the San Diego of the ’40s ― said he planted the idea with then-State. Sen. Jim Mills for the creation of MTDB, now the Metropolitan Transit System. He was also among the chief advocates for downtown renewal, the revitalization of Balboa Park, community-oriented policing and the adoption of the city’s first no-smoking ordinances.

Williams served three terms on the board of supervisors beginning in 1983 and remained its only Black member until 2023. He led the creation of a new Office of AIDS Coordination in the Health Services department, pushed for emergency freeway call boxes in the pre-cell phone era, supported a program for teen fathers in schools, and continued his anti-smoking crusade. In 2020, the county reestablished a Human Relations Commission originally created during his tenure as supervisor and named it after Williams.

Williams received an honorary doctorate in human relations from SDSU in 2007 and, in his ‘90s, was a regular visitor to the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, now part of Global Campus. He was a lifetime member of the SDSU Alumni Association, which named him to the Distinguished Alumni of the College of Arts and Letters in 2003 and selected him for its Diversity Award in 2010.