Research shows state’s strategy for river cleanup may be all washed up

Data from a five-year study indicates the unwanted debris is closely connected with another major societal problem.

This is an expanded version of an article originally published in the Spring 2025 issue of SDSU Magazine.

If you’re hoping to stop trash from flowing down rivers into the ocean by blocking it at the storm-drain stage it helps to know if that’s where most of it is coming from.

Turns out it’s not.

Hilary McMillan, professor of water resources in the San Diego State University geography department, led a NOAA-funded project to identify the main sources of trash in the San Diego River. Their hypothesis, she said, was storm drains “are one source of trash, but we didn’t think it was the main source.”

They were right. Through a combination of their own capture nets in the river and surveys by the San Diego River Park Foundation, McMillan and her students concluded anywhere from 79 to 92% of the trash ― plastic bags, cups and lids, food wrappers and the like ― can be traced to the flood plains along the river and to direct dumping, often adjacent to homeless encampments.

Capture devices will be required in California in five years. They will “help a little bit, but it’s not going to prevent most of the trash getting into the river,” said McMillan.

Findings were published in March in an article for Earth’s Future, an open-access journal of the American Geophysical Union, in a paper with contributions from faculty members and graduate students across three departments at SDSU. Data were collected over five years ending in 2023.

Consumer plastics as a source of debris and “now ubiquitous in urban rivers,” as the paper states, were a key area of investigation for their potential harm to marine life, coastal habitats and even human health, as the substances can be ingested by fish.

Other items ranging from cigarette butts and straws to clothing and mattresses can be found in urban waterways.

In 2015, the State Water Resources Control Board adopted a policy aimed at zeroing out the trash carried into ocean waters, bays and estuaries by 2030. The policy requires local jurisdictions to use “full-capture” systems in storm drains to block trash as small as 5mm found in runoff. It’s the same goal exemplified by those “No Dumping -- Drains to Ocean” pavement stencils and signs seen around California storm drains for decades.

However, full capture systems don’t stop trash from being dumped into the river next to homeless encampments, which are thought to be the source of 62 to 75% of the debris, according to the research findings.

In 2020 and 2021, when the number of unsheltered individuals in San Diego declined, dumping associated with homeless encampments also declined. The trend reversed post-COVID when pandemic shelter assistance programs wound down.

“This result highlights that homelessness is not simply a humanitarian crisis but also an acute environmental crisis,” the paper states. Additional materials are swept in after storms when the river level rises.

A critical source of data to quantify the sources of trash came from River Park Foundation volunteers, who head to the floodplains twice weekly for cleanup projects. “What we found is that is really critical in San Diego,” McMillan said, “because that’s really the only way that trash can get out other than being washed into the ocean. If they didn’t do those cleanups then there could be up to 50% more trash in the river than there is today.”

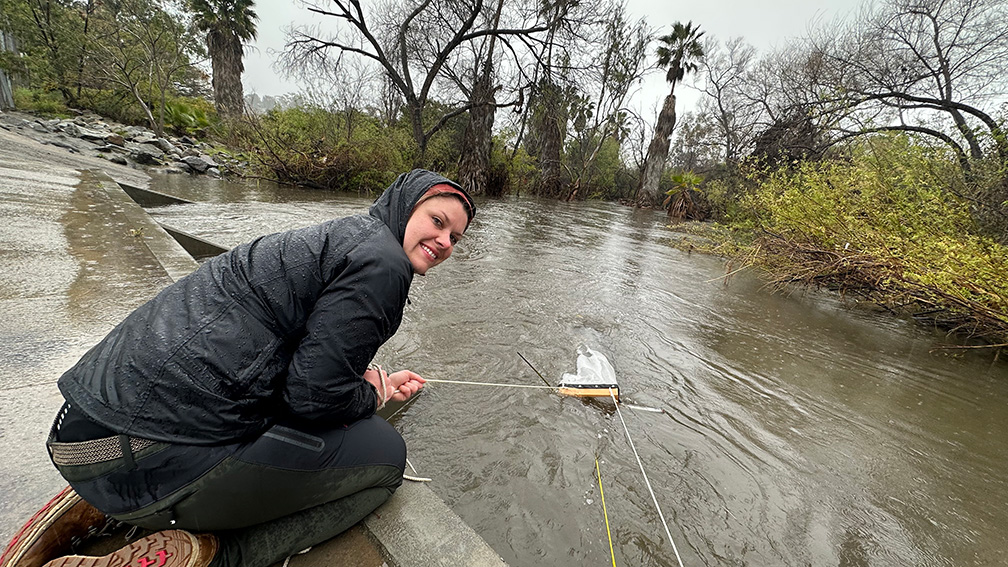

SDSU students also went into the field themselves to investigate on 18 occasions, using homemade trawl nets, lowered into the water to take samples.

McMillan’s paper says the findings from the San Diego River apply to other urban waterways.

SDSU in 2021 received nearly $300,000 in funding from NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to conduct the research under the agency’s Marine Debris Program. Housed within the U.S. Department of Commerce, research by NOAA and its academic partners supports the conservation and management of coastal and marine ecosystems and resources in addition to its better-known weather forecasting functions.