The Time Machine

SDSU biologists have collected specimens from every corner of the Earth for decades: It’s all in the Biodiversity Museum.

FOLLOWING A PATH outlined by railroad tracks, Marshal Hedin found himself deep inside a dark, cramped tunnel in a remote part of North Carolina. He examined the sides of the tunnel and, with the aid of a headlamp, spotted what he came looking for. Suddenly, he heard a whistle in the distance. The sound echoed through the hollow cavity, a warning that grew louder as the ground began to tremble. In a split second, Hedin pressed himself against the curved wall of the tunnel, motionless as the train barreled by. He clutched a precious vial in his hand.

The veteran field researcher quite often finds himself in precarious situations such as this. He braves each bold adventure with the same seemingly simple goal: to find spiders.

Hedin is a biology professor who joined the faculty of the College of Sciences in 1999. A year ago, he took on the role of director of SDSU’s Biodiversity Museum, a veritable natural history museum that houses more than 100,000 specimens that have been collected and acquired over the past 127 years. While Hedin’s speciality is arachnids, the museum’s shelves, drawers, cabinets and even ultracold freezers are filled with plants, insects, birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians from around the world.

“It’s important to preserve these samples because they provide a window into the past,” Hedin says. “I see biologists as stewards of the planet, including biodiversity that has been collected and preserved. It is our job to maintain this diversity, actively using specimens now but also carrying them to the future.”

This practice has become a dying art, as many universities and organizations have dissolved their collections due to a lack of resources. SDSU is the only university in San Diego with a museum of its kind. Over the years, curators have obtained specimens through the San Diego Zoo, SeaWorld, the San Diego Natural History Museum, donors and fieldwork like Hedin’s. Stored across several climate-controlled rooms in the Life Sciences South building, the specimens are safeguarded by Hedin and four other curators to ensure they can be used for research, teaching and public outreach in perpetuity.

SDSU alumnus Eric Ekdale (M.S., ’02), the mammals curator and a biology lecturer, started his career in the Biodiversity Museum. He now manages a collection that includes the skulls of an orca and an endangered Sumatran rhino, pelts from tigers and arctic foxes, and preserved bats and gophers, among hundreds of other samples.

“When I was a master’s student, my desk was actually right here,” Ekdale says, gesturing to the skull of a young Indian elephant. “We have a really wonderful collection to show San Diego State students the great diversity of life on Earth and hope that this fosters a real appreciation of the natural world.”

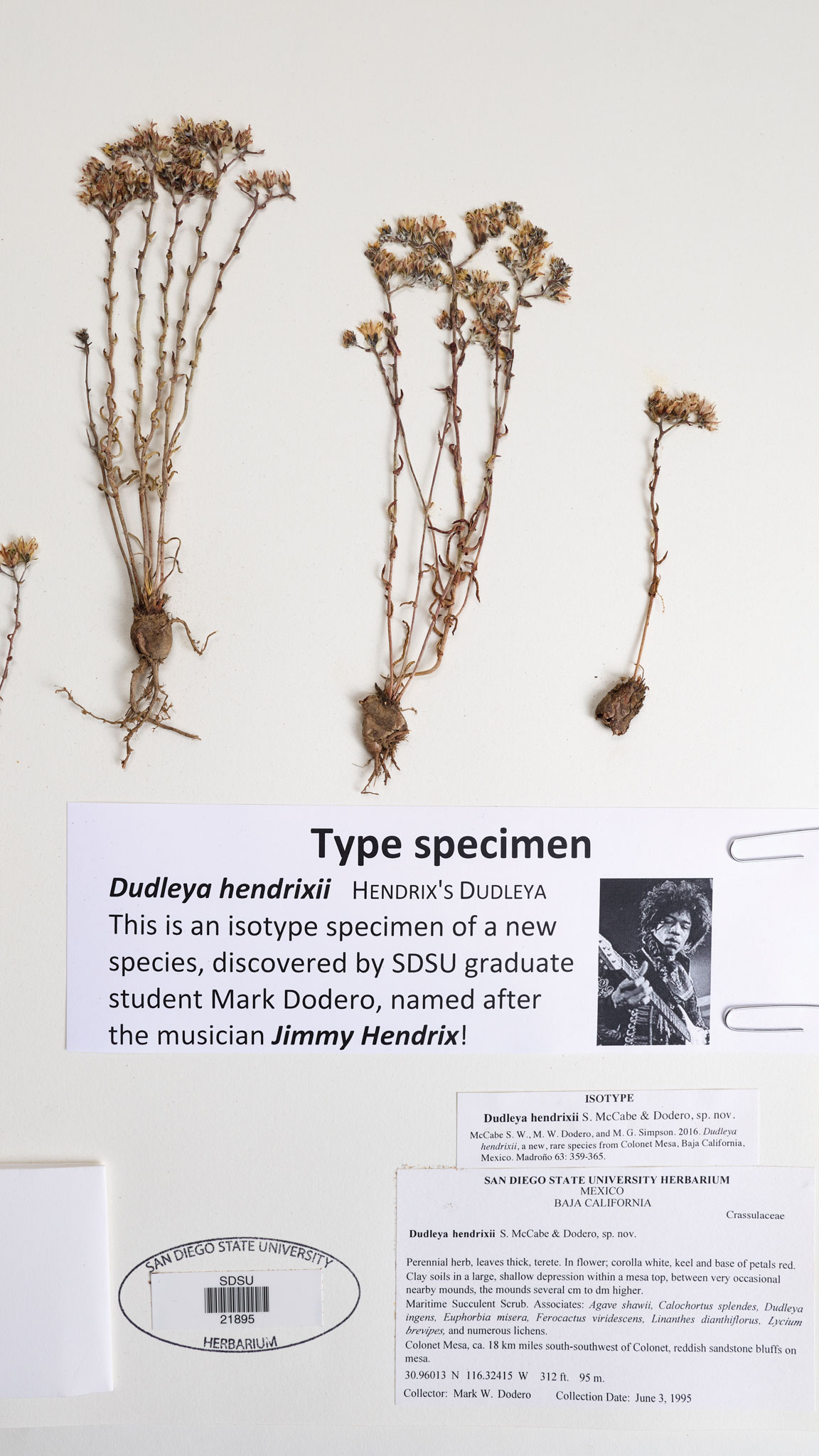

The collection helps students learn how to identify organisms, providing tangible examples to supplement lessons taught in class. Through research experiences facilitated by faculty, students have the opportunity to directly contribute to the museum’s repository. In 1995, grad student Mark Dodero was in Baja California searching for various plants when he stumbled upon a new species. He called the herb Dudleya hendrixii, after the legendary musician Jimi Hendrix. Dodero just happened to be listening to him at the time.

Discovering new species is just one way research promotes conservation in San Diego and beyond. Specimens, including cases of delicate blue Sonoran butterflies, provide insight into what life was like in the past, but they also act as a gauge for the current state of global ecosystems.

“We’re losing species at an alarming rate, 100 to 1,000 times faster than normal rates of extinction,” Ekdale says. “If we want to know what we’re losing, we have to know what we have and where to prioritize spending our time and money and resources.”

Open the image full screen.

Open the image full screen.Assistant professor Kinsey Brock, who serves as curator of the reptiles and amphibians collection, is doing that in her own backyard. Over the summer, she jarred her first samples of non-native urban lizards in San Diego. By comparing these newly collected Italian wall lizard specimens to their ancestors back in Italy, she and her students hope to understand how organisms adapt to swift environmental change.

“Historically, we haven’t sampled cities too often because we think of them as these unnatural places that are only for humans, but nothing could be more untrue,” Brock says. “My goal is to start collecting extensively across California cities so we have historical records of urban biodiversity in the future.”

Work like Brock’s also calls attention to species that are threatened. Inside the museum’s insects and arachnids collection are the few known samples of Hypochilus bernardino, a lampshade spider, that was gathered by Hedin. With an abdomen the size of a pencil eraser and legs that stretch out the circumference of a half-dollar, this species has been found only in a single small creek drainage in California’s San Bernardino Mountains.

“They prefer cool, shaded places, but the forest they live in is drying out and burning,” Hedin says. “They have nowhere to go. That is the only place they live.”

The lampshade spider isn’t alone. The Guam rail, a small terrestrial bird, is now extinct in the wild. SDSU professor Roger Carpenter studied the species in the ’60s and brought several back to campus from Guam, long before the bird was endangered. While conservationists are now attempting to boost the population’s numbers through captive breeding programs, the specimens remain as key witnesses to the effects that human and natural forces can have on entire species and their habitats.

“We have the time machine, the archive of biodiversity to inspire students,” says Kevin Burns, the museum’s birds curator. “If we’re going to get past the biodiversity crisis we’re in, we need that sort of education.”

Open the image full screen.

Open the image full screen. Open the image full screen.

Open the image full screen. Open the image full screen.

Open the image full screen. Open the image full screen.

Open the image full screen. Open the image full screen.

Open the image full screen. Open the image full screen.

Open the image full screen.

Using this time machine, researchers are sometimes able to bring the past back to life, so to speak. One “resurrected” species, found by professor emeritus and herbarium curator Mike Simpson, is Cryptantha wigginsii, or Wiggins’s popcorn flower. After studying the taxonomic literature, Simpson realized this plant species, previously thought to have been collected only once in 1931, was actually present among the university’s collection. After an in-depth investigation by colleagues at other California herbaria, Simpson realized that Wiggins’s popcorn flower, although rare, was still living in parts of California and Baja California.

“We thought it had never been collected elsewhere or at any other time after that initial find in the ’30s,” Simpson says. “Since then, now that we have a search pattern for it in the field, we have found several other populations, and now we know the general habitat where it grows.”

Having a suite of information available online was key to enabling this discovery, demonstrating just how vital digitization is to preservation. Nearly 100% of the university’s herbarium is digitized and imaged on the Consortium of California Herbaria, thanks to an instrumental National Science Foundation grant spanning from 2018 to 2022. Now, researchers can better locate and study the habitats of endangered species and notice key patterns such as plants flowering earlier due to warming caused by climate change.

In addition to the herbarium, collection data of all the museum’s specimens are in the process of being transcribed and will be available online. DNA sequence data may be linked to that collection information as well. This will allow people worldwide to explore the museum collections more easily than ever before.

“Collections are only great when more people have access to them,” Burns says. “We’re getting everything online now so that if someone wants to see a particular species or use data or get DNA, they know to come to us.”

The Biodiversity Museum isn’t available just to biologists: It’s open to anyone with the curiosity to experience it. Individuals, small groups or even classes from local schools can arrange a visit by reaching out to Hedin at [email protected]. And if asked, he just might have a story to share about one of his expeditions.

To visit the Biodiversity Museum, contact Marshal Hedin at [email protected].